World War I had a profound impact on Oregon. Above, clockwise from top left: Claude Beck of Portland (Army); Andrew Johnson of Phoenix (Air Corps); Ralph Gilliam of Wolf Creek (Navy); Revel Bower of Hopewell (Marines). (Oregon State Archives photos)

World War I had a profound impact on Oregon. Above, clockwise from top left: Claude Beck of Portland (Army); Andrew Johnson of Phoenix (Air Corps); Ralph Gilliam of Wolf Creek (Navy); Revel Bower of Hopewell (Marines). (Oregon State Archives photos) World War I turned Oregonians away from reform and back to more intense environmental transformations for the purposes of economic growth and war production. Heightened European demand for wheat and wood led to increased production in the fields and forests of Oregon.

Spruce Production Division

Airplane manufacturers wanted the light and strong wood of Sitka spruce trees, which grew especially well in coastal environments, including on lands that the U.S. government had removed from the Siletz and Grand Ronde Indian Reservations and sold to timber companies. To supplement private timber company production, the federal government in 1917 established the United States Spruce Production Division, which sent more than 7,500 soldiers into Oregon coastal forests to cut down spruce trees for the war effort. The war also brought changes to the ports of Astoria, Coos Bay, Tillamook and elsewhere on Oregon’s coast and the Columbia River, as the federal government’s Emergency Fleet Corporation contracted with a dozen shipyards to build wooden and steel ships. The increased demand for wartime material led to a shortage of labor, which briefly empowered workers and their unions. Timber workers in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) went on strike in the summer of 1917, demanding shorter hours, more pay and better working and living conditions. Timber companies refused, and the federal government stepped in, creating the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen (the 4-L), an industry-wide, timber company-friendly union that prohibited strikes, demanded loyalty pledges and instituted eight-hour days and better conditions. The 4-L undermined support for the IWW while government officials, politicians, law enforcement and vigilante groups attacked union members and officials.

End of Economic Boom

Workers suffered further with the end of the war in 1918: the international market for wood and wheat contracted, economic growth slowed and more workers competed for fewer jobs. The economic boom was over, but wartime production left behind logging equipment, shipyards, agricultural machinery and other tools and infrastructure that soon would transform Oregon’s environments again.

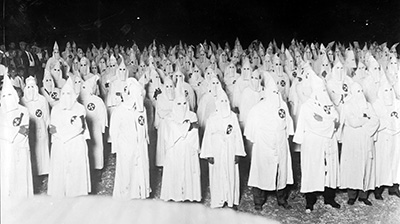

The Ku Klux Klan was a powerful force in Oregon during the 1920s as reactionary groups pushed back against progressive reforms. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

The Ku Klux Klan was a powerful force in Oregon during the 1920s as reactionary groups pushed back against progressive reforms. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)The immediate postwar period in Oregon brought a reaction against progressive reform and expanded efforts by some Oregonians to marginalize and exclude others. By 1920, the momentum for reform had slowed. In the 10 years following World War I, Oregonians voted on 89 ballot measures, compared to 147 measures in the decade before the war. Some of those initiatives, along with a variety of other laws and actions, sought to more closely define which peoples and cultures did and did not belong in Oregon. In 1922, voters approved the Compulsory School Bill, which required all students to attend public schools—a direct attack on Catholic schools and Oregon’s Catholic communities. The next year, the state legislature passed discriminatory laws that banned religious garb in schools (another assault on Catholic culture) and allowed city governments to deny business licenses to Japanese immigrants. The state legislature also passed a law prohibiting “aliens ineligible for citizenship”—especially Japanese immigrants—from purchasing or leasing land, an act that denied such immigrants equal participation and ownership in the agricultural transformation of Oregon’s environments. A variety of organized groups and civic associations supported these exclusionary efforts, including the American Legion and, most infamously, the Ku Klux Klan, which became a powerful political and social force in Oregon beginning in 1921. Some of this reactionary tide was pulled back—the Supreme Court ruled the Compulsory School Bill unconstitutional in 1924, and the Oregon Klan disintegrated by the end of the decade—but these exclusionary efforts left a hateful mark on the state’s history.

Discrimination also took more violent forms. The laws directed against Japanese Oregonians stayed in effect, and Japanese communities faced repeated harassment and violence, such as a 1925 incident in which a mob expelled Japanese workers from Toledo. Black Oregonians faced similar discrimination, including legal segregation, “sundown laws” that threatened them with violence if they remained in certain towns after dark, and real estate practices that restricted where they could live. Native Oregonians, too, were further marginalized. Native peoples were ineligible for American citizenship until 1924; Native children were forced into boarding and day schools that prohibited Native languages and dress; and Native peoples were prohibited from leaving reservations, which in western Oregon dramatically shrank in the aftermath of the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887, which allocated some reservation lands for ownership by tribal members, but sold most of the land as “surplus” to the highest bidder.

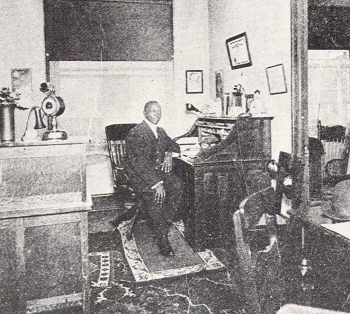

The

Advocate newspaper served as an influential voice of the black community in Portland beginning in 1903. (Courtesy of blackpast.org)

The

Advocate newspaper served as an influential voice of the black community in Portland beginning in 1903. (Courtesy of blackpast.org)These Oregonians resisted such marginalization. Native Oregonians survived and thrived: some retained title to their lands and integrated into mainstream Oregon society, while others found ways to preserve their culture. Other peoples also protected their families and cultures by sustaining independent ethnic communities, such as Portland’s three different Chinatowns or the Japanese schools that prospered in Salem, Hood River and elsewhere. Black communities thrived with independent civic organizations, churches, and businesses, and they advocated for equality through such means as the Advocate newspaper and the Portland National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)—the first NAACP chapter west of the Mississippi River. Oregonians also made two symbolic yet important political steps toward equality: in 1926, they repealed the section of the state constitution that excluded Blacks from Oregon, and in 1927, they overturned the state constitution’s prohibition of Black and Chinese suffrage.

By the late 1920s, Oregon had transformed in ways that could seem contradictory. Reformers had created the Oregon System and passed hundreds of initiatives and laws that sought to improve state society and environments. But those efforts only went so far. Many Oregonians rejected not only radicalism and reform, but also ethnic groups and communities that some White, Protestant Oregonians believed too foreign, strange, or unassimilable. Oregon’s landscapes bore the marks of this exclusion, such as the limits on Japanese ownership of land. Environmental conservation efforts also revealed other contradictory characteristics of these reforms. For example, Oregon established its first state park in 1922 and Oregon’s senior U.S. senator, Charles McNary, co-sponsored a federal act in 1924 that encouraged forest fire protection and reforestation. But McNary’s bill also avoided federal regulation of private harvesting practices, leaving timber companies in Oregon essentially free to cut as much as they wanted wherever they wanted. And the state park system had its origins in the State Highway Commission, whose central purpose was to build more, better, faster roads that cut through forests and farmlands. For Oregonians in the 1920s, these did not seem like contradictions, but rather evidence that they could and should reform, improve and control Oregon’s social and natural environments.

Next: Confidence Amidst the Crises of Depression and World War II >