A "Hooverville" of squatters' shacks stand along the Willamette River in Portland during the Depression in 1936. (Wikimedia Commons)

A "Hooverville" of squatters' shacks stand along the Willamette River in Portland during the Depression in 1936. (Wikimedia Commons) Oregonians’ confidence in and enthusiasm for control of nature continued even as the world crashed into economic catastrophe and global conflict. The Great Depression was particularly severe in Oregon’s cities, with massive unemployment in manufacturing and the service industries and the appearance of “Hoovervilles” in Portland’s Sullivan Gulch and the “Hotel de Minto,” a shelter for young unemployed men on the top floor of Salem’s city hall. The Depression hit rural areas, too, as prices, production and employment crashed in Oregon’s forests, mills, farms, fisheries and ranches. In Mill City, for example, the A.B. Hammond Timber Company mills quickly cut back the work week to 20 hours, then 10 hours, and finally shut down operations in 1935. Oregonians showed remarkable resilience and confidence in the face of this economic catastrophe. In rural areas, they turned to Oregon’s rich environments, relying on subsistence farming, fishing, hunting, and gathering and creating bartering economies that supported their communities. In towns and cities, municipal governments, civic organizations and other groups provided food and relief work for the unemployed. But the depth and severity of the Depression overwhelmed such noble efforts.

The New Deal

New Deal programs, such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA), put unemployed people back to work constructing public works projects. Above, the lobby of the Timberline Lodge, built by the WPA on Mt. Hood in the 1930s. (Oregon Scenic Images collection)

New Deal programs, such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA), put unemployed people back to work constructing public works projects. Above, the lobby of the Timberline Lodge, built by the WPA on Mt. Hood in the 1930s. (Oregon Scenic Images collection) At the urgent demand of many Oregonians, the federal government stepped in with the New Deal, which provided relief, assistance, and action. The government encouraged workers to join unions and provided assistance to farmers through the Soil Conservation Service and the Rural Electrification Administration. Some federal programs were directed at Native peoples. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 halted the allotment of reservation land, provided credit opportunities and funds for the purchase of additional lands, and provided a path toward federally-recognized self-government and economic development, like that followed by the Warm Springs tribes, which incorporated as the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation in 1937. Native Oregonians also participated in federal work programs including the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Public Works Administration (PWA). These and many other agencies provided paychecks and left a permanent mark on Oregon’s society and landscape. The CCC built trails, fire lookouts, warming shelters and more in Oregon’s forests; the WPA constructed Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood, hired artists and writers for cultural projects and created other employment opportunities; and the PWA built parks, schools, and government buildings, constructed bridges connecting Highway 101 on the coast and added other infrastructure throughout the state.

Some of these federal projects radically changed Oregon’s environments, especially Bonneville Dam, funded by the PWA and built by the Army Corps of Engineers between 1933 and 1938. Bonneville Dam created a 48-mile-long reservoir on the Columbia River, improved navigation, and generated electricity, but it also damaged salmon habitats. Water projects bloomed during the New Deal: the Bureau of Reclamation completed the Vale-Owhyee Project in the mid-1930s, creating more than 24,000 acres of irrigable farmland by the end of the decade, and federal studies of the Columbia River and its tributaries promised more river development for irrigation, hydropower, flood control and more. These studies, projects and programs represented an optimistic confidence that by transforming and controlling nature, Oregonians could overcome any obstacle, even the Great Depression.

World War II

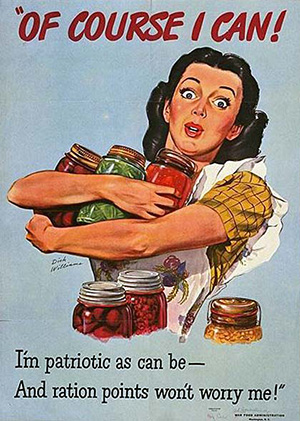

Rationing food and other products became a frustrating part of everyday life for Oregonians during World War II. (Image no. ww1645-73 courtesy Northwestern University)

Rationing food and other products became a frustrating part of everyday life for Oregonians during World War II. (Image no. ww1645-73 courtesy Northwestern University)

The Depression was eclipsed by the even greater cataclysm of World War II, which ended the economic catastrophe and impacted Oregonians in a variety of ways. More than 2,800 Oregonians died and 5,000 were wounded in the line of duty, and six people died when a balloon bomb floated over the Pacific Ocean from Japan and exploded in Bly in May 1945. The U.S. military built training camps and facilities throughout the state, including Camp Adair north of Corvallis, Camp White near Medford and Camp Abbott (which later became the resort village of Sunriver). Oregonians rationed food and fuel, staffed lookouts to protect forest resources, bought war bonds, saved and recycled metal and rubber and mobilized into civilian defense and air patrol units. They also worked long hours producing war materiel in existing factories, like the Thomas Kay Woolen Mill in Salem that ran three shifts to make Army blankets, and in brand-new facilities, including the Kaiser shipyards in Portland, which produced 455 ships and employed tens of thousands of workers during the war.

The war presented both opportunities and challenges to women and minorities in Oregon. The Bracero program brought more than 15,000 Mexican contract laborers to Oregon to plant, weed and harvest crops. Although they generally received better wages than in Mexico, Bracero workers faced racism, poor working and living conditions, and broken promises that they would be paid when they returned home. Thousands of Blacks came to work in Portland, where they found discrimination and an acute housing crisis. These problems were only partially alleviated by the rapid construction of Vanport, which provided homes, schools, nurseries and other services to 35,000 residents, 35% of whom were Black, and all of whom lived directly in the path of the Columbia River, which flooded and destroyed the city in 1948. Women also found work at the Kaiser shipyards, the Kay Woolen Mill and other manufacturers supplying the war effort. Despite persistent sexual harassment and unequal treatment—at the end of the war, they were the first to be fired—women proved the value of their work to themselves and to others.

Oregonians of Japanese descent endured particularly tragic discrimination during World War II. Beginning in April 1942, Japanese Oregonians—both immigrants who were prohibited by federal law from American citizenship as well as their children, who were birthright citizens of the United States—were forcibly evacuated from their homes in Portland, Hood River and throughout western Oregon, crowded into unsanitary transfer facilities, and sent to concentration camps in California, Idaho and Tule Lake, just across the southern Oregon border in California. At the same time, hundreds of Japanese Oregonians enlisted and served in the armed forces. When the camps closed and the war ended in 1945, Japanese Oregonians found themselves unwelcomed in their former homes, and many decided they could not return. But almost 70% did go back, because they—like Latino and Latinas, Blacks, women and everyone who had helped Oregon prosper during the war—rightfully called Oregon home.

A 1941 law related to logging operations aimed to maintain forest growth but widespread environmental damage continued as the race for profits remained the top priority. (Image no. HSTC146, courtesy Salem Public Library, Special Collections)

A 1941 law related to logging operations aimed to maintain forest growth but widespread environmental damage continued as the race for profits remained the top priority. (Image no. HSTC146, courtesy Salem Public Library, Special Collections) All Oregonians lived and worked in landscapes that had radically transformed in just a few decades. A single generation had seen wagon trails turned into railroads, animal power replaced by mechanized farm equipment, rivers dammed and rerouted, deserts irrigated, swamps drained, and astonishing quantities of lumber, food crops, livestock, fish and minerals produced from Oregon’s environments. Forests, fields, rangelands and waterways had industrialized, and Oregon more generally urbanized: in 1870, more than 90% of Oregonians lived in rural areas, but by 1930, the numbers of urban and rural residents were about equal.

Oregonians knew that such transformations could have negative effects, but they were confident they could minimize such consequences through reform and management. For example, in 1941, the state legislature passed the Oregon Forest Conservation Act, which required commercial logging operations to leave enough trees standing and/or plant new trees to maintain forest growth. Such efforts seemed to show Oregonians that not only could they overcome natural obstacles, but they could control and eliminate those obstacles. The end of economic depression and the war unleashed this confidence, and Oregonians found new and dramatic ways to assert control over nature. But such efforts, they soon learned, also had dramatic consequences.

Next:

Section III: Postwar Boom