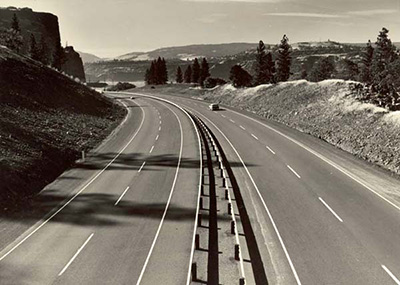

Federal aid fueled construction of freeways across the country in the decades after World War II. Shown here is Interstate 80N near Mayer State Park along the Columbia River. (Oregon State Archives photo 6624)

Federal aid fueled construction of freeways across the country in the decades after World War II. Shown here is Interstate 80N near Mayer State Park along the Columbia River. (Oregon State Archives photo 6624)Although confident that they could and should control Oregon’s environments, Oregonians also were anxious that the years after World War II might bring a return to the Great Depression or some other calamity. Just the opposite, it turned out: Oregon’s population and economy, like the rest of the nation, boomed. In 1940, the federal census counted 1,089,684 people in Oregon; by 1960, 1,768,687 people called Oregon home. Between 1945 and 1965, Oregon’s per capita income more than doubled and Oregonians cashed in their paychecks, war bonds and savings to buy cars, radios, refrigerators, washing machines, and, most importantly, houses. Real estate developers and home builders went on a construction spree, expanding cities, towns, and suburbs. Eugene, for instance, added 4,717 acres between 1950 and 1960, and Corvallis grew by more than 3,000 acres in that same decade. An increasingly dense network of roads and highways, including Interstate 5, connected these places and facilitated economic growth.

Tribal Impact

The smooth asphalt freeways and freshly-painted housing developments suggested that all Oregonians shared in and enthusiastically embraced this growth. But this appearance of consensus was forced upon some Native Oregonians through a process called tribal termination, by which the federal government sought to eliminate its trusteeship of Native lands and force the assimilation of Native peoples. Beginning in 1953, the U.S. Congress passed a series of laws that effectively ended federal recognition of tribal sovereignty and terminated the federal government’s responsibility to oversee and protect the lands, resources and interests of the Klamath and all Native groups west of the Cascades (the Warm Springs and Umatilla Reservations successfully prevented termination). The laws brought disastrous results: reservation lands were sold off, private speculators swindled Natives out of their land and property, Natives lost all services (such as health and education) formerly provided by the federal government, tribal governments disbanded, and Native communities scattered. The problems with termination suggested tension and trouble under the surface of Oregon’s postwar growth and confidence.

Environmental Impact

The Dalles Dam on the Columbia River is one of many postwar boom projects designed to master Oregon's rivers. The dam resulted in the flooding of Celilo Falls, an important part of Native American culture. (Oregon Scenic Images collection)

The Dalles Dam on the Columbia River is one of many postwar boom projects designed to master Oregon's rivers. The dam resulted in the flooding of Celilo Falls, an important part of Native American culture. (Oregon Scenic Images collection)Pursuing broader economic growth and inspired by new technologies, Oregonians expanded and intensified their efforts to master Oregon’s rivers, fields and forests in the two decades after World War II. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Bureau of Reclamation, and local utility companies built dozens of dams, from massive structures like the 260-foot-high concrete The Dalles Dam on the Columbia to smaller projects like the 78-foot-high earthen fill Keene Creek Dam on the Rogue River. Oregon’s farmers, chambers of commerce and civic groups cheered these river development projects, which promised flood control, improved navigation, inexpensive electricity, pollution mitigation, recreational opportunities and irrigation. While irrigation allowed farmers to control the timing, quantity and distribution of water in their fields, new chemical herbicides helped them manage weeds, and powerful insecticides effectively eliminated—for a short time—grasshoppers and other pests. These technologies, along with field burning, fertilizers, new tractors and combines and other investments, produced impressive results: for example, between 1945 and 1965, Oregon yields of field crops (barley, corn, hay, hops, oats, peas, rye, sugar beets and wheat) increased by 65% and production grew by 50%. Oregon timber production also increased: from 6,046 million board-feet in 1945 to 9,394 million board-feet 20 years later. Chainsaws, diesel-powered tractors and trucks and improved mill technology and processes facilitated this leap in production, as independent loggers and timber companies large and small supplied local, national, and international lumber markets. While technology increased efficiency, increased production also required the labor of tens of thousands of workers in forests, fields and pastures. In 1959, the U.S. Census of Agriculture counted 16,332 hired farm workers in Oregon, more than half of whom worked as seasonal labor.

Many of Oregon's old growth forests were harvested in a postwar push for more timber production. (Oregon Scenic Images collection)

Many of Oregon's old growth forests were harvested in a postwar push for more timber production. (Oregon Scenic Images collection)These efforts to master nature produced worrisome consequences for both Oregon’s environments and its peoples. As the growth in timber production began to exhaust the supply of timber on private lands, logging shifted to federal Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management public lands. Old growth forests were to be "converted" into tree farms and accessed by thousands of miles of logging roads; a 1956 forestry report called for nearly 15,000 miles of new access roads in Oregon’s national forests. Such practices produced unsightly landscapes, upset complex ancient forest ecosystems and damaged fish habitat in streams and rivers. On Oregon’s rivers, dams blocked salmon migrating to and from the Pacific Ocean, and fish hatcheries, fish ladders and other technical solutions only partially mitigated the loss in salmon populations. Dams slowed and warmed rivers—another problem for salmon—and inundated some communities and fishing sites with water; the most infamous example is Celilo Falls, drowned by The Dalles Dam in 1957.

Changes in Oregon’s agricultural landscapes revealed other problematic consequences—political and cultural, as well as environmental—from the transformations of the post-war period. While farm production and yields increased, the state’s agricultural character underwent a fundamental shift: by 1970, only 5% of Oregonians were farmers, as more people moved to Oregon’s towns and cities for work. This change was particularly obvious west of the Cascades and especially in the Willamette Valley, which lost 20% of its farmland to residential, commercial and industrial development between 1950 and 1965. Such development gobbled up farmland and other open spaces, overwhelmed sewer and water systems, and polluted Oregon’s water and soil with sewage and industrial contaminants. Changes to farming also raised concerns in the 1960s about the efficacy and safety of pesticides, herbicides and other chemicals that had been used to increase agricultural production. Moreover, these shifts in Oregon’s economic and demographic character revealed increasing concentration in the Willamette Valley not just of Oregon’s population, but also political and economic power. Oregon’s urban and rural environments were undergoing a remarkable transformation, and not always for the best.

Next: The Oregon Story and Other Narratives >