Governor Tom McCall looks at Cannon Beach’s Surfsand Motel in 1967. The owner, Bill Hay, wanted this beach area for the use of motel guests only. He set up a log perimeter and instructed his "Cabana Boys" and other employees to tell people who were not staying at the motel to leave the "private beach." The action exposed a loophole in existing state law and sparked a legislative conflict about public access to beaches. The Beach Bill was the product of the debate that pitted proponents of property rights against those favoring more public access protections. (Courtesy of Oregon Historical Society)

Governor Tom McCall looks at Cannon Beach’s Surfsand Motel in 1967. The owner, Bill Hay, wanted this beach area for the use of motel guests only. He set up a log perimeter and instructed his "Cabana Boys" and other employees to tell people who were not staying at the motel to leave the "private beach." The action exposed a loophole in existing state law and sparked a legislative conflict about public access to beaches. The Beach Bill was the product of the debate that pitted proponents of property rights against those favoring more public access protections. (Courtesy of Oregon Historical Society) These problems attracted the attention of a growing number of Oregonians, including some in positions of power, who supported a series of innovative and landmark environmental protection initiatives. Pollution was a particularly visible problem on the Willamette River, where industrial pollutants, sewage, and other contaminants led to unsafe water quality, especially during drier months. During the 1960s and 1970s, the Oregon State Sanitary Authority and its successor, the Department of Environmental Quality (established in 1969), strengthened and enforced efforts to limit pollution from Willamette River cities and industries, especially pulp and paper mills. By 1972, all municipalities and all but one pulp and paper mill met pollution treatment requirements. The state also sought to reduce other kinds of waste and encourage conservation: the “Bottle Bill” of 1971 established a deposit and return system for beverage containers; the “Bicycle Bill” (also 1971) required jurisdictions building roads, streets, or highways to also include facilities for bicycles and pedestrians; and state agencies, as well as some private businesses, implemented a variety of energy conservation measures.

The Oregon Story

Other environmental protection efforts of the time sought to preserve open spaces for public enjoyment and recreation. In 1967, the “Beach Bill” established that all of Oregon’s beaches, from the water to the dunes, were open to the public and were not for private ownership and development, expanding and strengthening existing protections established in 1913. Six years later, Oregon established a groundbreaking statewide land-use planning system that required all cities and counties to create zoning ordinance and long-range land-use plans. These plans established urban growth boundaries to regulate sprawl and set goals in 19 areas, including energy conservation, preservation of agricultural and forest lands, and air, water and land resource quality. Taken together, these and other environmental protection initiatives represented what then-Governor Tom McCall called “The Oregon Story”: a belief that Oregonians should take innovative action to improve the quality of life in their state.

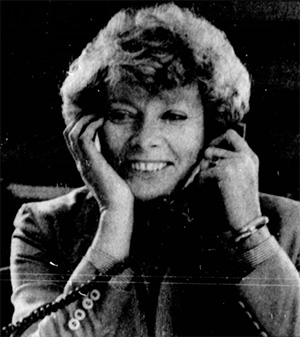

Oregon Secretary of State Norma Paulus, shown here in 1980, became the first woman to be elected to statewide office in 1977. (Courtesy of

Willamette Week)

Oregon Secretary of State Norma Paulus, shown here in 1980, became the first woman to be elected to statewide office in 1977. (Courtesy of

Willamette Week) Other Oregon Stories also were being written during the 1960s and 1970s, as minorities, women and other marginalized groups continued to assert their power and equality. The ongoing women’s rights movement secured significant political victories, including the state legislature’s vote to ratify the federal Equal Rights Amendment, the election of the first woman to statewide office (Norma Paulus, elected Secretary of State in 1977), and state legislation that prohibited discrimination against women in employment and retirement, removed marital status or cohabitation as a defense against rape, and more. Blacks in Oregon had achieved important political victories in the two decades after World War II, including state laws prohibiting discrimination in housing, employment and public accommodations. That political work continued through the following decades, along with protests, community organization and activism in groups like the Black United Front. Such activism confronted school segregation, police brutality, and other persistent forms of discrimination, including issues of environmental justice. Black Oregonians resisted “urban renewal” projects that destroyed Black homes and businesses, and they fought back against disproportionate levels of pollution in Black communities–for example, the high loads of toxins in Portland’s Columbia Slough, a waterway generally neglected by Oregon environmentalists focused on more “natural” rivers and streams.

Native Oregonians, too, fought back against discrimination and marginalization through activist groups, in tribal communities, and individually. East of the Cascades, the Warm Springs tribes developed successful timber operations and the Kah-Nee-Tah Resort, and the Burns Paiute Tribe secured federal recognition and reservation lands in 1972. Over the next two decades, the terminated tribes west of the Cascades successfully campaigned to restore federal recognition of tribal sovereignty: Siletz (1977), Cow Creek (1982), Grand Ronde (1983), Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw (1984), Klamath (1986), and Coquille (1989). Latino communities in Oregon continued to grow, developing a variety of cultural, educational, and political organizations, including Pro Fiestas Mexicanas, the Valley Migrant League, and Colegio César Chávez. By 1980, 5.4% of Oregon’s population was nonwhite, compared to 1.2% 40 years earlier. Through political activism, community organization and evolving cultural heritage, these communities contributed their own narratives to an increasingly diverse Oregon Story.

Rural vs. Urban

Rural communities dependent on timber chafed under new regulations designed to limit environmental damage. Shown here is the Georgia-Pacific wood products mill in Toledo. (Oregon Scenic Images collection)

Rural communities dependent on timber chafed under new regulations designed to limit environmental damage. Shown here is the Georgia-Pacific wood products mill in Toledo. (Oregon Scenic Images collection)Much of that Oregon Story was being written in, by, and for the urban residents of the Willamette Valley, the center of the state’s political and economic power. But the narrative looked different in rural parts of Oregon. While urban areas grew and diversified, the rural population of the state remained relatively homogenous: only 20% of the Oregon’s nonwhite population in 1980 lived in rural areas. The Willamette Valley’s enthusiasm for environmental protection certainly affected rural Oregon communities, but those communities expressed far less enthusiasm for such regulations. Timber production remained vitally important, providing not only jobs in the woods and in the mills, but also revenue from federal timber sales to pay for schools and other public services. Although Oregon passed a comprehensive Forest Practices Act in 1971 that sought to protect soil, air, water and wildlife on both public and private land, the timber industry, state and federal regulatory agencies, and politicians alike continued to support the lucrative practice of clearcutting old growth forests. Land use planning found strong opposition in rural communities east of the Cascades and in southern Oregon. Voters in timber-dependent and ranching communities supported initiatives in 1976, 1978 and 1983 that would have rolled back Oregon’s comprehensive land use planning laws, but they were outnumbered by Willamette Valley opponents to the initiatives. By the 1980s, rural and urban Oregonians often were deeply divided over the meaning of The Oregon Story.

Next: The Gaps Widen >