Environment

The northern spotted owl was listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1990, setting off a conflict between environmentalists and those concerned with the loss of timber industry jobs. (Wikimedia Commons)

The northern spotted owl was listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1990, setting off a conflict between environmentalists and those concerned with the loss of timber industry jobs. (Wikimedia Commons) In the 1980s and 1990s, the divisions among Oregonians seemed to widen, including differences in perceptions and uses of Oregon’s environments. The divisions became most obvious in fights over Oregon’s old growth forests. An economic recession in the early 1980s, coupled with the introduction of labor-saving computerized technology, led to mill closures and layoffs; in 1982, forest work employed 20% fewer people than just 10 years before. Some of those jobs returned in the mid-1980s as the economy improved, demand for timber increased, and logging on federal lands, especially in old growth forests, jumped to record levels. This raised worries among some scientists and others concerned about the loss of wildlife and old growth forests. The controversy crystalized around the northern spotted owl, whose population serves as an indicator for the ecological health and complexity of the old growth forests where it lives. In 1990, the owl was listed as a threatened species under the 1973 Endangered Species Act, requiring action to protect the owl and its habitat. Four years later, the federal government adopted the Northwest Forest Plan, which significantly reduced logging on federal lands. The management plan contributed to ongoing job loss in the timber industry, where the workforce already was shrinking due to logging and milling technology.

Oregonians also saw more conflicts over dams, irrigation projects, and other river development schemes that negatively affected fish habitat. In the 1990s, a variety of salmon populations were designated as threatened or endangered, leading to more regulations on fishing, hydroelectric power generation, and irrigation, and affecting the management of the Columbia and other Oregon rivers. In the news media and often on the ground, it appeared that such measures pitted rural Oregonians, whose communities depended on farming, logging and other forms of natural resource extraction, against urban Oregonians, who generally supported efforts to preserve the state’s environments for wildlife and recreation.

Cultural

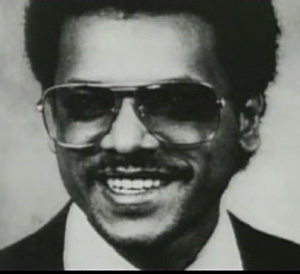

Divisions among Oregonians became even more pronounced around other transformations in Oregon society. As it had throughout its history, Oregon attracted new immigrants from different backgrounds, and the state’s population continued to diversify, with 7% of Oregonians identifying as nonwhite in the 1990 census, compared to 5.4% 10 years before. Minorities in Oregon achieved important measures of progress in the 1980s and 1990s, from the election of the first Blacks to the state legislature and statewide offices to the establishment of Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (PCUN), a Latino forest-and-farm-worker union. But minority populations continued to experience discrimination, marginalization and even hatred. Racist skinhead groups developed in some Oregon communities, including Portland, where a skinhead murdered Ethiopian exchange student Mulugeta Seraw in 1988. Skinheads also murdered two Salem residents in an apartment firebombing in 1992: Hattie Mae Cohens, a 29-year-old Black lesbian, and Brian Mock, a 45-year-old gay man.

The 1988 murder of Ethiopian exchange student Mulugeta Seraw by Portland racist skinheads was part of a larger backlash against anti-discrimination laws. (Wikimedia Commons)

The 1988 murder of Ethiopian exchange student Mulugeta Seraw by Portland racist skinheads was part of a larger backlash against anti-discrimination laws. (Wikimedia Commons) These murders occurred within the context of a conservative backlash against the gay and lesbian rights’ movement, which had secured notable victories in the 1970s and 1980s, including limited anti-discrimination laws in Portland (1974), Eugene (1977), and at the state level (1987). Some Oregonians opposed such developments and presented voters with anti-gay rights ballot measures: in 1988, voters repealed the state’s efforts to prohibit discrimination against gays in state employment, but in 1992, 1994 and 2000, Oregonians rejected ballot measures that sought to restrict civil rights protection based on sexual orientation and, more generally, discourage homosexuality. Most of the opposition to these initiatives came from urban areas, while more voters in rural Oregon supported them and passed local anti-gay rights ordinances. The state legislature and court system overturned these city and county measures—another example, some rural Oregonians said, of the increasing cultural and political chasm between the urban Willamette Valley and the rest of the state.

Funding

Oregonians also divided over public spending, taxes, and economic differences more generally in the 1980s and 1990s. Following a national trend that started in the late 1970s and continued into the 1980s, a fiscally-conservative anti-tax movement developed in Oregon that focused especially on cutting property taxes. Such taxes supported schools, social services and state programs directed at the conservation of Oregon’s environments, but many Oregonians regarded their contribution as too onerous, especially in Portland, where property values and taxes had increased rapidly in the 1980s.

By 1989, Oregon property taxes were the 7th highest per capita in the United States. In 1990, voters approved Measure 5, an initiative that constitutionally limited property taxes; seven years later, voters approved Measure 50, which capped annual increases on property taxes. Together, these initiatives decreased how much of their personal income Oregonians paid to state and local taxes (from 12.1% in 1989 to 10.5% in 1999) and shifted the burden for paying for schools from local property taxes to the state general fund, which relied more and more on income taxes. Oregon voters also overwhelmingly defeated sales tax initiatives in 1985, 1986 and 1993, leaving the state dependent on income taxes to fund education, environmental conservation and preservation programs and other government functions.

The Oregon tax revolt led to funding challenges for public schools in Oregon. Shown here is Jordan Valley Elementary School. (Oregon Scenic Images collection)

The Oregon tax revolt led to funding challenges for public schools in Oregon. Shown here is Jordan Valley Elementary School. (Oregon Scenic Images collection) Those taxes came from vastly different income levels that largely fell along an urban/rural divide. The historic concentration of wealth in the Willamette Valley was well established by 1970, when the Portland area had the highest median income level, while the seven counties with the lowest levels were located outside the Valley. That division remained firmly in place 30 years later: Washington, Clackamas and Yamhill counties had the three highest median income levels, while Wheeler, Lake and Curry counties had the three lowest. At the end of the 20th century, it seemed that Oregon’s people were as divided in economic, political and cultural issues as they were in their perceptions and uses of Oregon’s environments.

Next: Bridges and Divides >