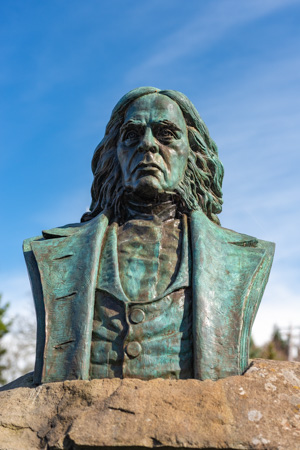

A bust of John McLoughlin at the viewpoint of Willamette Falls on the Willamette River in Oregon City. (Oregon Scenic Images collection)

A bust of John McLoughlin at the viewpoint of Willamette Falls on the Willamette River in Oregon City. (Oregon Scenic Images collection) The Americans’ belief in the righteousness of managing nature through agriculture, coupled with a belief in the righteousness of Christianity, confronted the lifeways and worldviews of Native peoples in Oregon. While McLoughlin developed his claim in the area around Willamette Falls, American newspapers in 1833 circulated reports of a small group of Nimiipuu who came to St. Louis looking for Bibles and Christianity. For Americans steeped in the evangelical fervor of the Second Great Awakening, such reports confirmed their calling to spread the Gospel. The Methodists first answered the call in 1834, sending the preacher Jason Lee, his nephew Daniel, and three laymen, who established a mission on the Willamette River about 13 miles north of what is now Salem. Two years later, an ecumenical Protestant party led by Dr. Marcus Whitman and his wife, Narcissa, settled near the Blue Mountains of northeastern Oregon to evangelize among the Cayuse, Umatilla and Nimiipuu. Fathers Francois Blanchet and Modeste Demers arrived in Oregon in 1838, establishing Catholic missions first on the Cowlitz River and then among retired French-Canadian HBC employees and their families living at French Prairie, in what is now St. Paul. These missionaries brought not only Bibles and Christianity, but also farming tools and agricultural practices: the gospel of progress through management of nature.

These evangelizing efforts failed to convert Oregon’s Native peoples to a new faith in great numbers, but the missions drastically changed life in Oregon. Protestant missionaries in particular critiqued Native belief systems and insisted on the superiority of white agricultural settlement rather than Native seasonal rounds. They also contributed to the spread of disease and death among Native peoples. Even prior to regular contact with white explorers, fur traders, sailors and farmers, Native peoples experienced the devastating effects of smallpox, measles and other Old World diseases. That devastation increased in the early 1830s, when a series of malaria epidemics decimated Chinookan and Kalapuyan societies along the lower Columbia River and in the Willamette Valley, killing perhaps 90% of the Native population. Missionaries and their families contributed to these epidemics both through their own biological presence, and by facilitating the immigration of more white families and the diseases they brought with them. Their reports and public presentations delivered back east trumpeted the agricultural potential of the Willamette Valley, where diseases had decimated Native populations, leaving behind the rich, open fields produced by Native burning practices. Those reports, along with other positive accounts from Oregon boosters like Hall Jackson Kelley and John Wyeth, drew more and more settlers to the Willamette Valley, which held an estimated 150 Americans in 1841. The next year, more than 100 Americans migrated to Oregon, and approximately 900 more came the year after that. By 1845—just 11 years after Jason Lee arrived—the Willamette Valley was home to approximately 6,000 Euro-Americans and just 500 Kalapuyans. These emigrants to Oregon were part of a wave of mass migration that washed over the globe during the 19th century, when millions of settlers and workers from Europe and Asia descended on the American West, Australia, South Africa and elsewhere.

The Americans who came over the Oregon Trail in the 1840s traveled relatively lightly but carried weighty hopes for the future and strong beliefs about religion, society and nature. They came from the newer states of the Midwest and the Upper South—Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky and Missouri, especially. Most were Protestants, and they found in Oregon spiritual and material support from the missions that had shifted from saving Indian souls to encouraging White settlement. They traveled the Oregon Trail and settled in Oregon as patriarchal families, establishing extensive kin networks with distinct roles for women and men in family and work. These new Oregonians also had particularly strong ideas about racial hierarchies. Although very few held slaves, nearly all White Americans in Oregon believed that Blacks were inferior. White Oregonians also helped quicken the decline of Native populations. They poured into the Willamette Valley and took Kalapuyan land by “squatting,” claiming land for homesteads by virtue of the advances of American civilization and agriculture, preceding any legal action by the United States government towards Native lands.

Thousands of Americans packed their possessions into covered wagons and traveled the Oregon Trail in the 1840s. This covered wagon is at the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center at Flagstaff Hill near Baker City. (Oregon Scenic Images collection)

Thousands of Americans packed their possessions into covered wagons and traveled the Oregon Trail in the 1840s. This covered wagon is at the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center at Flagstaff Hill near Baker City. (Oregon Scenic Images collection) The new Oregonians brought with them plants, livestock, and agricultural techniques that remade the landscape in the image of the farms they had left behind back east. Americans tilled the land and built fences; they planted corn, wheat and vegetable gardens; they raised cattle, oxen and hogs. This resettlement of Oregon–for the country had once been the settled home of Native people–depended on the labor of Native peoples, hired to work fields that had been cleared by the burning practices of their parents, grandparents and ancestors. American resettlers concentrated on establishing subsistence farmsteads that would sustain their families and future generations. But the new Oregonians gradually cleared larger fields, built longer fences, and established sawmills, gristmills and granaries to prepare their products for market; these processes accelerated and expanded as farming and transportation technologies improved over the 19th century. These new Oregonians found willing buyers, too, especially when the California Gold Rush increased demand for Oregon’s wheat and wood. But even before 1849, American resettlers had remade the environment of the Willamette Valley with homesteads, vegetable gardens, tilled fields, fruit orchards and other signs of Euro-American cultivation and culture. In so doing, these new Oregonians acted out another aspect of their mid-19th century religious ideology: their understanding of the Biblical instruction to “have dominion” over nature. The changes they wrought transformed the environments upon which Native peoples had developed their seasonal rounds and other ways of thriving in their lands.

These white resettlers quickly turned to economic and political organization to reaffirm their view of nature and their ambitious claims to Oregon. They especially valued domesticated animals, which not only provided meat and milk, but also represented control over the wild nature that surrounded them. In 1837, a group of settlers formed the Willamette Cattle Company and sent a party led by former fur trapper Ewing Young to California to buy cattle. Young returned with more than 600 longhorns, which increased the availability of valuable livestock, transformed the valley’s landscapes by eating native plants and enriched the company’s investors, including Young. He died in 1841 without a will or any heirs, causing a minor legal emergency. To determine what to do with Young’s cattle-based estate, White settlers elected a judge and three law enforcement officials. In short, cattle—more specifically, the value white settlers placed on them—gave birth to political organization in Oregon country.

This mural by Barry Faulkner in the Senate Chamber of the Oregon State Capitol in Salem depicts the Wolf Meetings. (Oregon Scenic Images collection)

This mural by Barry Faulkner in the Senate Chamber of the Oregon State Capitol in Salem depicts the Wolf Meetings. (Oregon Scenic Images collection) Livestock also instigated the next big move toward government in 1843, during what would later be known as the “Wolf Meetings.” During those meetings, Willamette Valley settlers not only created a tax-funded bounty system meant to destroy wolves, bears, and other predators preying on livestock, but also decided to found a Provisional Government. The Wolf Meetings alienated many British citizens living in Oregon, and nearly all Britons abandoned the meetings, rejecting what was a clearly an American-led effort to establish American-style government in anticipation of the official extension of American authority. Those settlers were soon overwhelmed by rapidly increasing numbers of Americans, who expanded the role of the Provisional Government and called on the United States to assert more authority in Oregon. The Americans especially wanted to guarantee their extensive land claims: up to a full square mile of land under the Provisional Government’s code of laws—which, of course, were not recognized by Great Britain, which still jointly occupied Oregon with the United States. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 provided some security by finally settling the boundary between U.S. and British claims at the 49th parallel. But Americans in Oregon wanted more: to become a U.S. territory, which would bring federal recognition of their land claims and, more importantly, federal intervention against Native peoples. It was their and the nation’s “Manifest Destiny”—the popular mid-century explanation of and justification for what many white Americans believed was the natural, inevitable and righteous expansion of the United States to the Pacific Ocean.

A deadly conflict with the Cayuse people of the Columbia Plateau brought Americans in Oregon the territorial status, recognition and intervention they wanted. Since its founding in 1838, the Whitman Mission had produced more conflict than conversion: the Whitmans accused the Cayuse, Nimiipu, and Umatilla peoples of laziness and backwardness, while the Native peoples became frustrated with the missionaries’ abusive evangelism and the ecological destruction caused by increasing numbers of American settlers and travelers. In 1847, the tension boiled over into war. A group of Cayuse and Umatilla peoples, suspecting Marcus Whitman of causing a measles epidemic that killed more than 200 of their people, attacked the mission, killing a dozen whites (including the Whitmans) and taking 53 hostages. They eventually released the hostages, but not before white settlers in the Willamette Valley sent a volunteer militia on raids against the Cayuse demanding federal action and protection. The federal government responded in 1848 by passing the Organic Act, which created Oregon Territory, and by sending the U.S. Army to assist the white vigilantes, who returned to Oregon with five of the Cayuses involved in the Whitman attack. On May 24, 1850, after a two-day trial and 75 minutes of deliberation, a jury of twelve White men convicted the five Cayuses of murder, and they were executed on June 3. That same year, the U.S. Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Law, which legitimized existing land claims and allowed new white immigrant families arriving before Dec. 1, 1850 to claim up to 640 acres (later arrivals would get half as much land). Congress also authorized treaty commissioners to negotiate with Oregon tribes for their land, although that work did not commence until 1851, well after Congressional authorization of the distribution of Native lands. With official incorporation into the United States, the federal government’s commitment to obtaining Native lands, and their own land claims secured, the new Oregonians could continue to pursue their hopes for a better future and their vision for Oregon’s landscapes.

Next: Creating an Exclusive Paradise >