Chief Joseph led his Nez Perce people in war against the U.S. Army in 1877. (Wikimedia Commons)

Chief Joseph led his Nez Perce people in war against the U.S. Army in 1877. (Wikimedia Commons) Other peoples and cultures would have to make way for that particular vision. In the 1850s and 1860s, U.S. Indian agents and treaty commissioners secured agreements with dozens of Native tribes and bands throughout Oregon, sometimes through honest negotiations, but often by means of dishonest or willfully ignorant negotiations. These forced treaties ceded enormous amounts of Native lands and confined Native peoples to marginal territories on reservations. Treaties that were regarded as insufficiently generous to white interests often went unratified or simply ignored until government officials secured harsher terms requiring the sacrifice of more Native land. In addition to establishing reservations, the U.S. government also built military posts throughout Oregon to keep Native peoples separated from the growing numbers of White settlers. Devastated by disease and displacement, many Native peoples were forced to move to reservations, where some adopted sedentary agriculture and accepted as a necessity poorly-paid wage labor, while attempting to preserve their families, societies and cultures as much as possible.

Conflicts and Wars

Other Native peoples refused to tolerate White aggression and the ecological havoc wrought by Whites and the invasive plants and animals that came with them. In the 1850s in southwestern Oregon, bands of Shasta, Tututni, and other Native groups attacked White settlers and miners, responding to years of raids and violence against Native peoples and the destruction of the plants and animals on which they depended. The ensuing Rogue River Wars lasted until 1856, when the U.S. Army forcibly removed Native peoples to far-off reservations on the western side of the coastal mountain range. In the Great Basin in the 1860s, Northern Paiute bands raided miners, ranchers and other overland travelers who strained the region’s scarce resources. After a vigorous campaign by the U.S. Army in 1866–68, most Northern Paiute surrendered and moved to reservations, although some later joined the Bannock people of Idaho in their resistance to federal authority. Further south on the Oregon-California border, the Modoc War of 1872 pitted more than 1,000 U.S. soldiers against a few dozen Modoc warriors who could no longer tolerate the poor conditions at the Klamath Reservation. The Modocs held out for nearly six months before the U.S. Army finally chased them down, executing some of the leaders and sending the rest to far-away Indian Territory in Oklahoma. On the Columbia Plateau, White travelers, settlers and miners continued to strain the environment on which the Cayuse, Umatilla and Nimiipuu depended, leading to a series of treaties, reservations and finally conflicts: the Yakima War of 1855–58, the Nez Perce War of 1877, and the Bannock War of 1878.

By the end of the 1880s, multiple methods of force—treaties, displacement to reservations and violence—had removed Native peoples from their homes throughout Oregon. The Nimiipuu were scattered to different places: the Warm Springs and Umatilla Indian Reservations in Oregon, Colville Indian Reservation in Washington and Nez Perce Indian Reservation in Idaho. Some Northern Paiutes remained in the Burns area, while others moved to the Warm Springs Reservation, joining Wascoes and other people from the Columbia Plateau; other Plateau peoples were forcibly moved to the Umatilla Indian Reservation. Other tribes also lived on these reservations, as well as at the Klamath, Grand Ronde, and Siletz Reservations. Still other Native peoples, together as small communities or families or individually, lived away from reservations in or close to towns and urban areas. Hundreds of Native children were forced to attend and live at the Chemawa Indian School, established in Forest Grove in 1880 and moved to its present location north of Salem in 1885. In such challenging situations and environments, Native peoples would continue to claim their place in Oregon’s history, while their homelands became subject to the exclusive possession and control of White resettlers, prospectors and speculators.

Exclusionary Measures

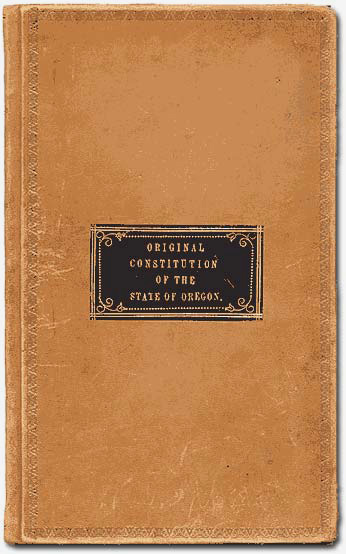

The cover of the original Oregon Constitution. Racist provisions were enshrined in the document. (Oregon State Archives photo)

The cover of the original Oregon Constitution. Racist provisions were enshrined in the document. (Oregon State Archives photo)The vision of civilization, agriculture, and progress embraced by White Oregonians also excluded other nonwhite peoples. From the earliest stages of American political organization in Oregon, White settlers took deliberate steps to keep out people of color. Even before Oregon became a U.S. territory, the Provisional Government enacted laws that banned both free and enslaved Blacks from Oregon and threatened to whip those who stayed. The territorial government reinforced these exclusionary efforts by barring nonwhites from testifying in court, and the Oregon Donation Land Law of 1850 excluded Blacks from its generous provisions. At the critical moment of statehood in 1857, Whites once again attempted to keep out Blacks: voters rejected slavery, but by an even greater margin they also reaffirmed the exclusion of Blacks from Oregon. The Oregon constitution thereby became the first state constitution to explicitly exclude free Blacks. White Oregonians made it clear that other nonwhite peoples also were not welcome: the Donation Land Law excluded Hawaiians, who had worked and lived in Oregon since the early 1800s, and the state constitution barred Chinese people from voting. White Oregonians wanted a White state, and they got one: according to the 1860 census, they made up more than 90% of the state’s 52,465 inhabitants, although that figure did not fully record the state’s Native population.

The Civil War and its aftermath confirmed that Oregon’s environments would be owned, cultivated and manipulated by Whites only. Oregon’s Democratic, Whig, Know-Nothing and Republican party leaders shouted at each other about abstract issues such as property rights and self-determination, but like their White male constituents who approved the exclusionary Oregon constitution, they generally agreed that the state must exclude both slavery and free Blacks. While other parts of the United States violently divided over slavery, the Civil War most directly affected Oregon by temporarily restricting the federal government’s negotiations and conflicts with Oregon’s Native peoples. Watching the Civil War from a distance, White Oregonians generally approved of the Union’s success, with isolated but notable expressions of Southern sympathy in Jacksonville and Eugene. But White Oregonians did not embrace the Civil War’s greater meaning for rights and equality. Instead, Oregonians passed laws that banned interracial marriage and required nonwhites to pay extra taxes. In 1870, they rejected the 15th Amendment, which protected the right to vote for all men, regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” White American settlers jealously guarded their agricultural paradise in Oregon.

Next: Expanding into New Environments >