“One thing is sure, we can’t do any worse than the men have done.” – Comment by newly-elected Umatilla "Mayoress"

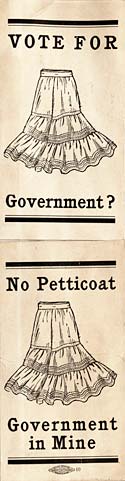

“One thing is sure, we can’t do any worse than the men have done.” – Comment by newly-elected Umatilla "Mayoress" An anti-suffrage advertisement. Many men believed women were not qualified to vote or hold office or that women would be tainted by the process. (Courtesy of University of Oregon Library)

An anti-suffrage advertisement. Many men believed women were not qualified to vote or hold office or that women would be tainted by the process. (Courtesy of University of Oregon Library)

After decades of struggle, women gained the right to vote in Oregon in 1912. Of course, the fight continued for woman suffrage on a national basis until the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1920. But beyond the right to vote, women were empowered by the movement in other ways. Many threw off societal limits on dress and behavior. Some threw their hats in the political ring and this led to instances of what became known as "petticoat governments" in Oregon. Here are three examples.

Umatilla

On December 5, 1916, the City of Umatilla elected an all-woman slate of candidates and received national newspaper coverage as the first “all female” city administration in the United States.

City of Umatilla Mayor Laura J. Starcher. (Oregon Daily Journal, December 17, 1916, page 14)

City of Umatilla Mayor Laura J. Starcher. (Oregon Daily Journal, December 17, 1916, page 14) The City of Umatilla had a population of 300 residents with approximately 200 voters in 1916. According to the newspapers, a group of woman grew tired of watching the town fall into disrepair and the loose enforcement of the laws. They decided they could do a better job of running the town. Their campaign prevailed with a clean sweep for the six female candidates. Laura J. Starcher defeated her husband for the position of mayor by a vote of 101 to 73. Elected to council were Gladys Spinning, Florence Brownwell, Anna Means, and Stella Paulu. Lola Merrick was elected treasurer and Bertha Cherry was elected recorder. Two male members of the council were holdovers (or as one newspaper put it “leftovers”) but the mayor did not give them any committee assignments.

The new administration got to work improving the water and electrical services, approved funds for street and sidewalk projects, and organized city “Clean up weeks.” Additional accomplishments included new railroad crossing signs, founding of a town library, monthly garbage collection and appointment of a city health official during the 1918 pandemic.

One of the more interesting policy decisions they made was not to hire a city marshal. The newspapers speculated that it was because they would need to appoint a man to the job, but they could have found a woman who was proficient in the use of a gun. Mayor Starcher said the expenditure of $57 a month was unnecessary in part because a deputy sheriff was on the streets daily and the city charter empowered any member of the council to make an arrest if needed.

Yoncalla

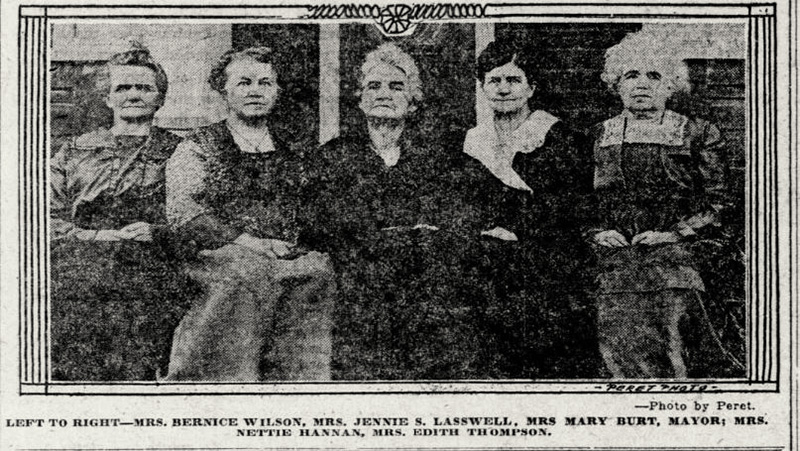

City of Yoncalla Mayor Mary Burt [center] led an all-woman city council after the 1920 election. (Morning Oregonian, Nov 10, 1920, page 4) Enlarge Image

City of Yoncalla Mayor Mary Burt [center] led an all-woman city council after the 1920 election. (Morning Oregonian, Nov 10, 1920, page 4) Enlarge Image Another petticoat government arose in the City of Yoncalla in Douglas County.

As the 1920 city election approached, it was reported that the male politicians in the community intended to let the incumbents of the various city offices hold over without opposition. One newspaper stated that the men were more concerned with state and national politics at this time. However, several women decided to organize a stealth campaign to elect a more responsive government. The male politicians were surprised when the ballots were counted and the results showed a clean sweep for the women. One of the newly elected council members was the wife of the mayor and, as the newspaper noted, this certainly disproved the old adage that “a woman cannot keep a secret.”

The previous administrations were described by the woman as “inefficient, allowing breaks in the sidewalks to go unrepaired, speeding automobiles were not controlled, streets were insufficiently lighted and that a general sickness in municipal affairs prevailed. We intend to study conditions and do all in our power to give the city of Yoncalla a good, efficient government.”

The mayor-elect, Mary (Goodell) Burt, was a native Oregonian and graduate of Pacific University in 1873. One of her classmates there was Harvey Scott, longtime editor of

The Oregonian and a strong opponent of woman suffrage in his day.

The newly elected council members were: Bernice Wilson, Jennie Laswell, Nettie Hanna, and Edith Thompson. Characterized by the newspapers, “as mature women,” they had all been active in community affairs before their election and were longtime residents.

The Oregonian reported in December, 1920 that the mayor and city council resigned their positions before the expiration of their terms. The men said they took this action to let the women begin at once their program of civic betterment and pledged their support of the new administration.

Burns

City of Burns Mayor Grace Lampshire got a big surprise on election day in 1920. (Morning Oregonian, November 25, 1920, page 8)

City of Burns Mayor Grace Lampshire got a big surprise on election day in 1920. (Morning Oregonian, November 25, 1920, page 8) Located out in the wide open frontier of eastern Oregon, the City of Burns elected a female mayor in 1920 without her even knowing.

The same year that Yoncalla voted for an all-female city administration there was an even more surprising result in the city election in Burns. Grace Lampshire was elected mayor even though she had no idea that she was running for office. Apparently, friends of Mrs. Lampshire decided she could do a good job as mayor and wrote her in on the ballot. When the results were tallied she had won!

The press, even on a national level, published numerous stories about the success women in Oregon were having in taking control of municipal governments. They often paired the stories of the Yoncalla election with reports of the news of Mrs. Lampshire’s election.

Grace had been a resident of Harney County since the early part of the century, having served as a teacher at Poison Creek north of Burns before her marriage to Edwin Lampshire. Unfortunately, he drowned just a few years later and she returned to her parents' home in Eugene. Grace returned to Burns around 1910 and married her former husband’s brother, J. J. Lampshire. She was active in a number of civic organizations and it was likely her hard work and success in these undertakings that led to the write in campaign.

Lampshire served a two-year term and then appears to have returned to a less public life. She can be found in later census records with her occupation listed as florist.

Next:

Ratification of Constitutional Amendments >