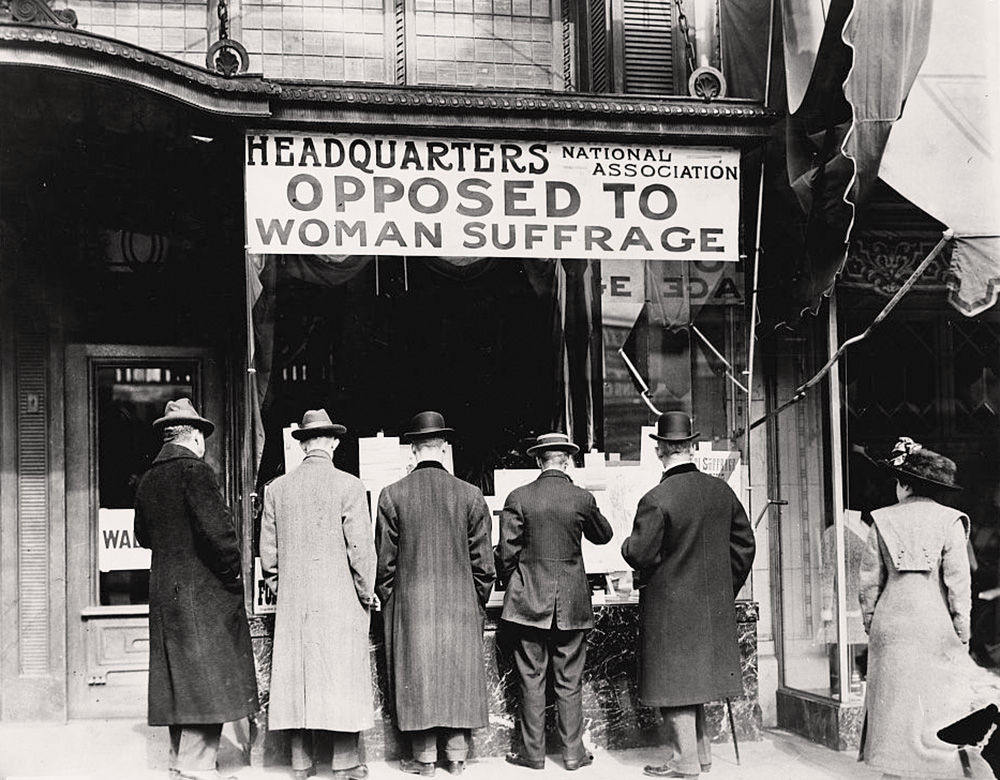

Resistance to woman suffrage was strong. This photo shows men surveying material posted in the window of the National Anti-Suffrage Association headquarters, ca. 1911. A curious woman looks on from behind. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

Resistance to woman suffrage was strong. This photo shows men surveying material posted in the window of the National Anti-Suffrage Association headquarters, ca. 1911. A curious woman looks on from behind. (Courtesy of Library of Congress) Resistance to the notion of woman suffrage was strong in the U.S., where arguments against opening the ballot box to women were often based on notions of hierarchy. Primarily that suffrage would upset the established social order that men – and many women – relied on.

One argument revolved around divinely ordained or pseudo-scientifically assumed separate spheres for the sexes. Many Americans held to the cult of domesticity, that a woman’s place was in the home with children. Some men even feared that by engaging in business or politics wives would become masculinized – and thereby feminize their husbands.

The argument that women were too emotional or frail to uphold their duty to vote circulated widely, as did the notion that women would lose the “privileges” of not serving in juries and not fighting in wars. Some religious and progressive suffragists believed that women were spiritually purer than men and would be sullied by the corrupting nature of politics. Indeed, many anti-suffragists claimed that the women who pushed for voting rights were somehow morally deficient.

Race and ableism were also factors in the propaganda of anti-suffrage, especially in the south. Opening the vote to women meant opening it for immigrants and women of color, which threatened the hegemony of Protestant white supremacy. Others held that including women in the voting pool would not improve the quality of the vote. These anti-suffragists believed that states should restrict the suffrage of those deemed “unfit” such as felons, individuals with intellectual disabilities, and women.

Coverture

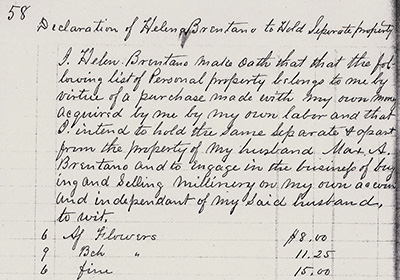

A page from an 1859-1902 Jackson County Register of Married Women's Property itemizes a woman's property separate from that of the husband. (Courtesy of Ben Truwe)

View Expanded Image

A page from an 1859-1902 Jackson County Register of Married Women's Property itemizes a woman's property separate from that of the husband. (Courtesy of Ben Truwe)

View Expanded Image Many notions of the anti-suffrage establishment in America stemmed from the colonial English system of coverture – whereby husband and wife are legally considered the same person. When women married, they fell under the “coverage” of their husbands, subsuming their rights and identity in the process. Married women were often unable to own property, enter into contracts, earn a salary, or receive an education without her husband’s permission. Because of coverture, many believed that married women had no need to vote because their husbands already could.

In the mid-19th century, the position of wives being akin to slavery gained popular opinion, and by the end of the Civil War 29 states challenged coverture with married women’s property acts. These usually passed in three phases: first allowing married women to own property, then to keep their own income, and finally to engage in business. Oregon passed its first women’s property act in 1878, and though these laws dismantled coverture, they did so in a piecemeal fashion. Laws denying women access to property remained in some states until the 1970s, and as of 2020 the Equal Rights Amendment, which would ensure equality of rights under the law regardless of sex, remains unratified.

Next:

Mass Media and the Colors of the Cause >