Coalitions

The Progessive Era represented a repudiation of the corruption and excess of the Gilded Age that preceded it. This illustration from an undated William Jennings Bryan campaign print laments the actions of the plutocrats and monopolists of the late 1800s. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

The Progessive Era represented a repudiation of the corruption and excess of the Gilded Age that preceded it. This illustration from an undated William Jennings Bryan campaign print laments the actions of the plutocrats and monopolists of the late 1800s. (Courtesy of Library of Congress) Universal woman suffrage was not a popular idea at the beginning of the women’s rights movement in the U.S. Early woman suffrage efforts were hampered by race and class divisions – conservative opinions argued that only white or landowning women should be able to vote. The wave of suffragist victories that swept the nation in the early 20th century, however, stemmed not from division but an ability to build partnerships with other reform movements. Suffragists like Esther Pohl Lovejoy and Alice Paul discovered that campaigns succeeded best with the support of broad coalitions and diverse groups of voters. Women’s rights groups also built strong relationships with the temperance and progressive movements, tied their agendas together and struggled for a common cause of social reform.

The Progressive Movement

The progressive movement took national politics by storm from the 1890s to the beginning of the Great Depression. A reaction against the excesses of the Gilded Age, progressivism sought to eliminate the political corruption and unregulated industry which led to urban squalor. Many progressives also sought to improve conditions for women and children, pushing for child labor laws and a woman’s right to vote.

Progressivism was an instrumental force in achieving national woman suffrage, though it had deeply divergent motivations. Many progressives were among the nation’s first feminists, espousing the radical notion that women deserved the same rights as men – though the largely white movement was often stymied by racism. The progressive movement was also deeply religious, energized by reform-oriented branches of Christianity and Judaism. These more religious progressives often believed women were spiritually purer than men, and therefore better equipped to vote on laws that fought corruption.

The Temperance Movement

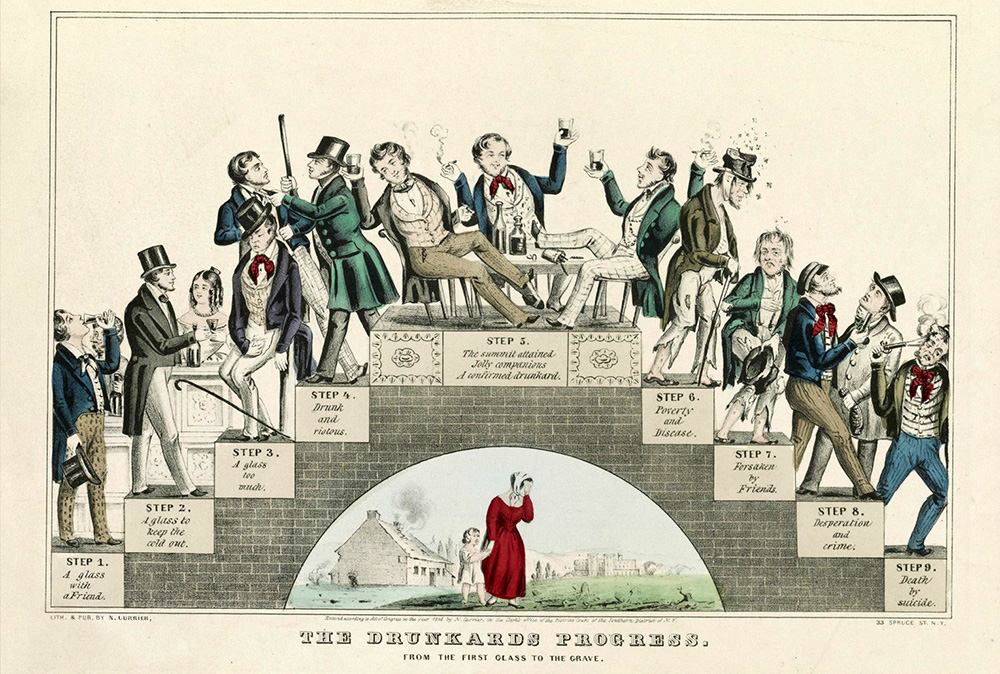

Temperance advocates argued that an innocent drink with a friend often led to tragic results. This 1846 lithograph by Nathaniel Currier illustrates the disastrous path. (Large image Courtesy of Library of Congress) M

Temperance advocates argued that an innocent drink with a friend often led to tragic results. This 1846 lithograph by Nathaniel Currier illustrates the disastrous path. (Large image Courtesy of Library of Congress) Many early feminists and progressives involved themselves in America’s Temperance Movement, which aimed to limit the widespread consumption of beer and liquor. By the early 19th century, the United States was gripped in an epidemic of alcoholism that created waves of domestic abuse and chronic poverty. Women and families, who were often economically dependent on men, could suffer because of the addictions of their husbands and fathers.

After the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, white social activists turned away from radical reforms like race or gender equality and promoted temperance instead. Though the temperance movement sought to deal with the very real problems of alcoholism, it was limited in scope. The movement primarily sought to change men’s behavior as voting heads of households, rather than give women equal access to the money, property, and rights which would make them independent of men.

Heavily supported by religious groups, especially Evangelical Protestants, the temperance movement grew, focusing on education and providing alternatives to alcohol. Portland’s many bronze drinking fountains are a product of the movement. They are known as “Benson Bubblers” after Simon Benson, the teetotaling philanthropist who paid for their installation in 1912.

Women and Prohibition

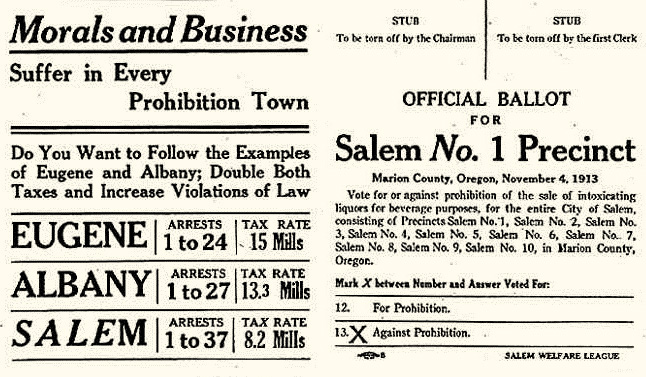

Opponents of prohibition stoked fears to encourage voters to block the effort. Beginning in 1904, an Oregon local option law gave communities the right to choose whether or not to ban alcohol. The law set off fierce debates over the issue. This mock ballot argued against prohibition in 1913. (Oregon State Library subject vertical files on prohibition, 1913) View Transcript and image

Opponents of prohibition stoked fears to encourage voters to block the effort. Beginning in 1904, an Oregon local option law gave communities the right to choose whether or not to ban alcohol. The law set off fierce debates over the issue. This mock ballot argued against prohibition in 1913. (Oregon State Library subject vertical files on prohibition, 1913) View Transcript and image Women were a driving force behind curbing alcohol consumption in the early 20th century. Organizations like the Anti-Saloon League and Woman’s Christian Temperance Union were fronted or run entirely by women. For many American women before the 19th Amendment, these movements were some of the few avenues for political action and social justice open to them.

Because women were some of the most vocal advocates of prohibition, anti-suffragists often used their views on alcohol to deny women access to voting rights. They stoked fears that woman suffrage would mean the end of alcohol, and the death of bars and breweries. These fears materialized as women gained the right to vote in some states, and then immediately passed laws limiting access to alcohol.

Not all women voted the same, though, and many rallied against the 18th Amendment which prohibited intoxicating liquors. Some joined social clubs and speakeasies where illegal drinks were sold, while others engaged in brewing bootleg alcohol in their own kitchens to get by in hard times. Some chose a legal route, and the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform organized in 1929. The WONPR successfully argued that prohibition encouraged crime and disrespect for the law – creating more problems than it solved.

Next: Oregon's Initiative and Referendum System >