Growing Pains Follow Military Build Up in Oregon

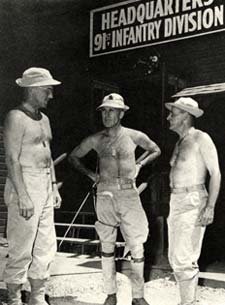

Military leaders talk at Camp White in the summer of 1942. Pictured are ADC Brigadier General Percy W. Clarkson, CO Major General Charles H. Gerhardt, and Brigadier General Edward S. Ott, Division Artillery Commander. (Image courtesy Camp White Museum)

Military leaders talk at Camp White in the summer of 1942. Pictured are ADC Brigadier General Percy W. Clarkson, CO Major General Charles H. Gerhardt, and Brigadier General Edward S. Ott, Division Artillery Commander. (Image courtesy Camp White Museum) The military build up before and during World War II profoundly affected Oregon communities as military cantonments and bases brought tens of thousands of soldiers, sailors, and marines to the state. The influx of people heated up the economies of communities long in the doldrums of the Depression as servicemen streamed to local towns in search of entertainment and services. Yet, growing pains followed for several cities as local populations mushroomed, not only with servicemen, but also with civilians filling new service jobs in the private sector and in the camps. Housing became scarce and expensive, schools were overcrowded, and crime rose as formerly sleepy communities buzzed with the frenzy of wartime boom towns.

Examples of Significant Military Facilities

Oregon played host to numerous military facilities during the war. The Astoria area was the home of Fort Stevens, Camp Clatsop, and the Tongue Point naval station while down the coast at Tillamook, the Navy built two of the largest wood-frame buildings in the world to house a fleet of blimps to patrol the coast. Large air bases were located at Portland and Pendleton. In fact, the daring pilots of the 1942 Doolittle Raid over Japan trained at the Pendleton facility. Marine barracks grew up on the edge of Klamath Falls while the Hermiston area became the site of the sprawling Umatilla Ordnance Depot with hundreds of bunkers designed to store a massive amount of munitions. But the largest impact resulted from the growth of three large training cantonments near Medford, Corvallis, and Bend, each dwarfing nearby towns.

From top to bottom: Insignia patches of the 91st Infantry Division; 70th "Trailblazer" Infantry Division; 104th "Timberwolf" Infantry Division; and 96th Infantry Division.

From top to bottom: Insignia patches of the 91st Infantry Division; 70th "Trailblazer" Infantry Division; 104th "Timberwolf" Infantry Division; and 96th Infantry Division. Camp White ballooned to 77 square miles and nearly 40,000 people at its peak, more than 16 times the area and three times the population of nearby Medford in 1941. By October 1942 the camp was ready to serve as a training center for the Army's 91st "Powder River" Infantry Division (and later the 96th "Deadeye" Infantry Division), with two ranges at the heart of the action. The Beagle Range was used to practice infantry drills such as taking enemy strongholds. It included concrete pillboxes, designed to simulate Nazi fortified coastal regions of Europe, that troops practiced manning and capturing, often with live ammunition. The Antelope Range included existing farm buildings and other specially constructed buildings to form a "Nazi Village." Troops practiced combat skills in a realistic setting as they stormed the town. According to military officials: "Realistic training means that a man who may soon face death in combat comes as close to it as he dares in training so that he may know what death looks like, how it sounds, how it smells."

Footnote

1

Camp Adair, consisting of 65,000 acres mostly in Polk and Benton counties north of Corvallis, was chosen in August 1941 after officials considered other locations in the state. The site was selected because of its proximity to railroad, water, and electric supplies and its mix of flat land and wooded rolling hills for training. Four divisions trained there: the 104th "Timberwolf" Infantry Division; the 70th "Trailblazer" Infantry Division; the 96th Infantry Division; and the 91st Infantry Division. The camp had 1,800 buildings, including barracks and mess halls, numerous office buildings, five movie theaters, seven churches, stores, a hospital, and a bakery capable of producing 35,000 loaves of bread a day. Training grounds, artillery ranges, and wooded hills covered almost 75% of the camp's area and included a simulated Japanese village where soldiers practiced for a possible future assault on Japan.

Footnote

2

Military officials established Camp Abbot, about 11 miles south of Bend, to serve as an Engineer Replacement Training Center (ERTC) in 1943, with soldiers first arriving for training in March. As many as 10,000 men could train at a time at the camp, with 90,000 men trained over its 14 months of operation. The typical 17-week combat engineering training cycle included three phases. The first focused on hand grenades and anti-tank grenades; defense against air, mechanized, and chemical attack; and rifle marksmanship. The second phase concentrated on demolition training to blast bridges and other structures. The final phase consisted of three weeks of field maneuvers carried out under combat zone conditions.

Footnote

3

Workers celebrate at a party thrown by the contractor after they broke a world record by pouring concrete for 24 igloos in 24 hours at the Umatilla Ordnance Depot in Sept. 1941. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c22730)

Workers celebrate at a party thrown by the contractor after they broke a world record by pouring concrete for 24 igloos in 24 hours at the Umatilla Ordnance Depot in Sept. 1941. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c22730) The Umatilla Ordnance Depot had a striking influence on Hermiston and nearby towns after the government announced the contract in December 1940 to build the world's largest munitions depot. Almost overnight Hermiston grew from 800 people to a boom town with 7,000 workers. They came from all over the country to build its magazines, shops, and warehouses and to drill deep wells and construct a 241 mile network of railroads and macadam roads to transport munitions. Construction went quickly as workers set world records pouring concrete. By the end of 1941 many construction workers left the area, replaced by those shipping, receiving, and storing munitions and other war related items on round-the-clock shifts.

Footnote

4 Boosterism and Dislocation

Boosters and town leaders were delighted at the thought of the increase in business that could follow the siting of a major military facility near their town. Restaurants, movie theaters, dance halls, bars, and shops would experience land office business from tens of thousands of servicemen, regular paychecks in hand, flowing into their downtowns. Farmers and ranchers knew vegetables, milk, eggs, beef, and other products would be in high demand. Local sawmills saw the potential for big orders of lumber and wood products to construct the hundreds of buildings such as barracks and mess halls that made up a camp. Construction workers would be needed in the early phases and various laborers would be needed later to work in camp laundries, bakeries, and related facilities.

Footnote

5

Neighbors gather at a farewell picnic north of Corvallis after 60,000 acres of agricultural land was taken in 1942 for development of the Camp Adair military cantonment. (Image 8123 courtesy Salem Online History)

Neighbors gather at a farewell picnic north of Corvallis after 60,000 acres of agricultural land was taken in 1942 for development of the Camp Adair military cantonment. (Image 8123 courtesy Salem Online History) But, not everyone was happy about attracting large camps to the area. Families and communities affected by the property condemnations needed to acquire the vast amounts of land for the camps suffered while business leaders rejoiced. Tight-knit rural communities such as Beagle with its modest farms and ranches north of Medford had little recourse. They were destined to lose family homes, incomes, and a way of life but couldn't complain for fear of appearing unpatriotic. Lawsuits brought by landowners against the government over the amount of compensation dragged on for much of the next four years. In the end, the small rural community was no match for the needs of the military and the enthusiastic support of local business leaders. The Army destroyed most of the farm and ranch buildings under the justification of "national security." Many were obliterated by bombardments that were part of artillery training.

Footnote

6

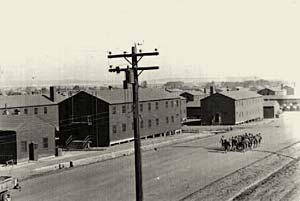

The barracks and the parade ground at Camp Adair as the cantonment was nearing completion. The camp had a profound effect on local communities like Corvallis, Albany, Monmouth and Independence. (Image 8105 courtesy Salem Online History)

The barracks and the parade ground at Camp Adair as the cantonment was nearing completion. The camp had a profound effect on local communities like Corvallis, Albany, Monmouth and Independence. (Image 8105 courtesy Salem Online History) Similarly, condemnations for Camp Adair uprooted and scattered about 6,000 people and wiped the community of Wells off the map. Many displaced land owners banded together to "protest the unfair and unjust treatment accorded us and other residents of this area in connection with the acquirement of the properties and the dislocation of the residents." Their chief complaint was that "the prices being offered do not represent fair market values plus the added consideration of being 'unwilling sellers.' Owners cannot relocate similarly with money received or offered." Other protests centered on the lack of advance notice to vacate, delays in payment, and unfair appraisal and inadequate payment for crops and farm improvements.

Footnote

7 Boom Towns

Once the farmers and ranchers had been removed from the land, the boom town atmosphere was set to begin as construction workers and the first waves of servicemen streamed into camps. According to Army descriptions of the effect of the Umatilla Ordnance Depot on Hermiston, "men who came and got work [had] $100 a week to spend. Their attempts to spend it made this peaceful village overnight into an overgrown carnival working a 24-hour shift. Hastily-erected lunch rooms and hot dog stands, soft drink and beer establishments, a movie, grocery stores, shoeshine stands, and meat markets played to long waiting lines." Camp Adair had a big influence on nearby communities too. Even early on, in August 1942, Albany, Corvallis, and Independence saw a 50% increase in business volume. Local restaurant and entertainment centers experienced 100% growth over a short period. More distant cities, such as Salem, 24 miles away, and Eugene, more than 40 miles away, also "felt the tide of Army arrivals."

Footnote

8

Housing conditions became so acute at Hermiston that authorities at the Umatilla Ordnance Depot experimentally converted igloos into housing quarters. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c22746)

Housing conditions became so acute at Hermiston that authorities at the Umatilla Ordnance Depot experimentally converted igloos into housing quarters. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c22746) Camp White caused explosive growth in the Medford area as the city's streets became "a sea of government green." In addition to nearly 40,000 soldiers at the camp, Medford drew a considerable influx of new civilian residents. Many worked in service jobs at the camp while others worked at the new businesses sprouting up to cater to servicemen. By late 1942, Medford's population grew to over 17,000, an increase of more than 50% over its 1941 population. Most took the changes in stride, accepting the confusion and crowding as a welcome change from the dark days of the Depression and proud to be a part of the nation's war effort. But the pace could be too much for some frazzled residents, such as the lunch counter waitress wildly rushing from customer to customer who exclaimed: "That cantonment! I'd like to never see another soldier. They're in here so thick I never get a second's peace."

Footnote

9 Crowding Problems

A federal government report from May 1942 said that "at the present time the rent situation in Hermiston is a serious problem. Tar paper shacks with almost no conveniences are renting for $18. Anything approaching a cabin in quality will rent for $25."

Housing proved a major problem. Living space became a luxury in Hermiston as longtime residents rented spare rooms in their homes as well as front lawns and vacant lots for trailer space. One farmer turned his 160 acres into trailer space to capitalize on the demand. The Umatilla Army Depot built barracks for 1,700 men but married men and their families needed space too. Even after many of the construction workers left town, Hermiston still experienced problems with high rents. A federal government report from May 1942 said that "at the present time the rent situation in Hermiston is a serious problem. Tar paper shacks with almost no conveniences are renting for $18. Anything approaching a cabin in quality will rent for $25."

Towns near Camp Adair encouraged residents to share or remodel their homes into space for the newcomers. Corvallis and Albany developed programs to build 100 new homes each, while Independence also added homes to cope with the influx. In Medford, construction workers typically lived in tents or trailers and then moved on after the camp was built. Soldiers, however, often brought their wives and families with them and needed more permanent housing as did the large numbers of civilian service workers streaming to the area. Creative property owners responded by building rooms in attics, basements, barns, and chicken coops. Many charged high rents before the federal Office of Price Administration developed controls implementing Congressional passage of the Emergency Price Control Act of 1942.

Footnote

10

The crowding sometimes brought friction between longtime residents and their new neighbors, both military and civilian. Some locals grew tired of waiting in long lines for services or crowding into movie theaters with hundreds of servicemen. In Medford, one serviceman recounted how he was "neatly crowded from a revolving stool at a cafe counter and sharply told, 'Soldiers should eat at Camp!'"

Footnote

11 One wife of a construction worker in Hermiston complained to Governor Sprague that her daughter was denied admittance to the local high school because of discrimination against newcomers:

The Honorable Governor

Sept. 2, 1941

Dear Sir:-

This is positively unnecessary. It is a matter of not crowding or making things a little tight for the children of the old residents here. There are two churches very near the school and the library that could be used - and then it is not unusual that two children sit in one seat, on portable chairs - and the shift system.

It is purely a matter of selfishness and partiality. The folks in Washington and other states don't treat the newcomer this way. It is purely a case of refusal to find a way to take care of the situation for the outsider. It is inexcusable and I pray you will write the Superintendent here, that he make more generous steps to give our children an education. It is unadulterated defiance, and unheard of in any part of our "land of the free."

The old timers here are benefitting greatly, financially, by filling their homes, woodsheds, chicken houses, pastures, front yards, with families working on the project, and charging plenty for the "shelters" and the merchants can't keep merchandise on their shelves in order to supply the demand of the workers, but they won't turn a hand to make life for our children a natural one.

Most Respectfully

Mrs. Joseph Swanson

Box 273

Hermiston, Oregon

Footnote

12

Governor Sprague responded by essentially blaming the federal government. Apparently, Hermiston was running out of funds to pay teacher salaries and other operating expenses because of the influx of students. Congress made provisions for such situations and Hermiston had applied for help months earlier. "Unfortunately," Sprague wrote, "the matter appears to be badly bogged down with bureaucratic red tape in Washington." He lamented that "this delay is inexcusable," but assured Swanson he would "do everything in my power to facilitate this matter to the end that the children in Hermiston will be able to get the education that is the rightful heritage of every American child."

Footnote

13Criminals Come to Town

Students crowd the halls at Hermiston High School in September 1941. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c22714)

Students crowd the halls at Hermiston High School in September 1941. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c22714) Big payrolls associated with large construction projects and camps could also attract undesirable people to the booming communities. The prime contractor project manager for the Umatilla Ordnance Depot, C.L. Fry, reported to Governor Sprague that "there is a definite increase in the daily number of strangers in Hermiston streets, not the working man type, but more of the questionable variety...." Some of the local businessmen were "of the opinion that the place is a good spot for a hold-up or robbery...." In fact, Fry wrote that some local businesses had seen their robbery insurance policies cancelled as a result of recent mail and service station hold-ups in Hermiston. The project generated a huge payroll of about $340,000 each week, with about 80% of the money handled by the local bank and other businesses. Worried this money would fall prey to criminals, Fry wrote to the governor that "it is our belief that a special squad of not less than six men [state policemen] should be assigned to duty at once to prevent further outbreaks of crime in this vicinity."

Footnote

14 The president of the First National Bank of Hermiston, F.B. Swayze, also wrote to Governor Sprague calling for state action to control traffic and crime problems in the booming city:

Charles A. Sprague, Governoer [sic]

October 3, 1941

We went through the payday for this week today. We had the bank full and a line on the sidewalk so we have a real necessity, whether we get protection or not. This afternoon two small children were hurt with a truck in front of the bank and were taken to the doctor's office. I have not heard how seriously. Right this minute, which is exactly eight P.M. I look out my window and the street is full of honking cars on the highway stopped for some reason of a traffic jamb [sic] or something that has happened in the next block down Main Street.

These men who have been attracted here by publicity are not local. They come from far away as well as near. They came to see how the rich picking looks and unless they are taken care of, they are not going to pass up as easy a proposition as this one here is. They are not scared away. They are still here and no one knows who they are plotting against all the time and when the next job may be pulled.

Very truly yours,

F.B. Swayze

Footnote

15

Related Documents

Letter from Charles Pray to A.C. Dunn

Letter from Charles Pray to A.C. Dunn, Oct. 6, 1941. Folder 15, Box 2, Gov. Sprague Records, OSA; Letter from Governor Sprague to F.B. Swayze, Oct. 8, 1941. Folder 15, Box 2, Gov. Sprague Records, OSA.

Notes