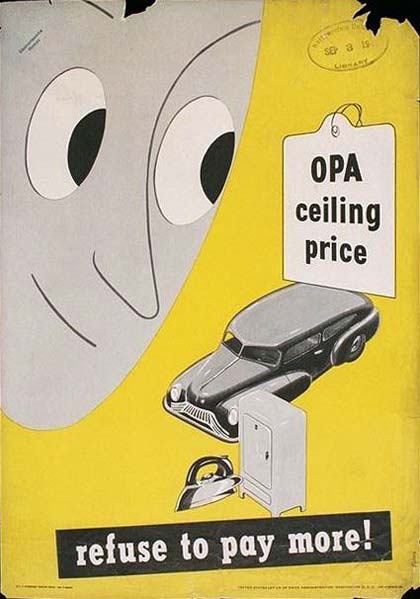

"Do Not Pay More Than the Top Legal Price"

Posters challenged housewives to take a price control and rationing pledge.

Pledge image courtesy Northwestern University Library "Inflation is nothing but a fancy term for rising prices. It is a complicated subject when professors start talking about it but it is simple for you and me." Thus read part of a suggested speech to be given by defense council workers.

Footnote

1 But despite government efforts to keep it simple, the price controls designed to fight inflation led to confusing regulations and mixed results. Price stability tended to be an early casualty in most wars and by 1942 a potentially dangerous inflationary pattern had developed in the United States. Decreasing supplies of civilian goods conspired with mounting war expenditures and consumer incomes, in a classic wartime supply and demand cycle, to raise prices at an alarming rate. The federal government responded with a complex system of price control along with related rationing and rent control programs.

OPA Takes a Larger Role

OPA regulations covered numerous consumer goods.

Graphic image courtesy Northwestern University Library

OPA regulations covered numerous consumer goods.

Graphic image courtesy Northwestern University Library The federal Office of Price Administration (OPA) took on the task of reining in rising prices in early 1942. In fact, the federal government had worked to control the cost of defense materials such as steel and aluminum for about two years following the defense build up in American industry after the outbreak of war in Europe, which had put the inflationary cycle in motion. A precursor to the OPA also engineered limited price controls on a number of products such as lumber, rubber and paper. But these measures proved inadequate and in January 1942 Congress passed the Emergency Price Control Act authorizing more stringent control of prices by the OPA. Three months later, President Roosevelt introduced a seven-point plan to control inflation. The plan, involving several federal agencies in addition to the OPA, called for heavier taxes, price control, stable wages, stable farm prices, war bond buying, rationing and less consumer credit. Part of the aim of the government was to siphon off much of the money going into workers pockets from the hot defense economy.

The imbalance was such that by 1943 Americans had more than 126 billion dollars after paying taxes to spend on only 89 billion dollars worth of goods. The difference, authorities reminded, was "37 billion dangerous dollars": "Industries which used to make things such as automobiles, radios, refrigerators and so on are now making tanks, guns, planes, and ammunition. So the things they used to make are not available for people to buy." At the same time, millions of workers left the labor market to join the armed forces, thus driving inflationary pressure on wages by causing a shortage. Officials pointed out that: "wage increases put still more pressure on prices and push them up faster still. And so on it goes, with prices and wages racing up the spiral. No one can ever quite catch up with the rising cost of living."

Footnote

2 General Max

The price control component of the Roosevelt's anti-inflation plan set up a General Maximum Price Regulation - soon to be known in wartime parlance as "General Max." This initiative in April 1942 froze most prices at the highest level reached as of March 1942. In response to what was called the "certainty of galloping inflation," General Max met with only limited success, in part because farm prices and workers' wages fell outside of its authority. The effort also fell prey to "growing complexity and unworkability" according to OPA Administrator Prentiss Brown. Each time the OPA allowed a price increase "to afford relief to a seller, a new regulation had to be written or an old one had to be amended." The thicket of regulations quickly grew more tangled to the point that, as Brown noted, "...the simplicity and understandability of the controls steadily diminished."

Footnote

3

Inflation Comparison

Many materials, such as steel and iron, that had been used for cars and other domestic products, were shifted to war production. Price controls kept a lid on inflation despite intense pressure caused by shortages. The comparison below shows inflation for four key materials.

| Steel | 334.6% | 0% |

|---|

| Copper |

170.4 | 14.3 |

|---|

| Tin |

223.7 | 6.6 |

|---|

| Iron | 303.6 | 14.6Footnote

11 |

|---|

Some manufacturers found ways around the restrictions by making small changes to their content or packaging, thereby allowing them to call old products "new" ones to avoid price controls. Others kept prices the same but reduced the quality. And still others eliminated traditional discounts or less expensive lines of products to keep profits high.

Footnote

4 Yet, a year after its inception, the limitations of the program needed to be kept in context according to Brown: "Had it not been issued, the cost of living would have risen, not the 10 per cent it has increased since May 1942, but 10 times 10 per cent."

Footnote

5 Statistics comparing the prices of controlled and uncontrolled retail food prices supported Brown's claim of partial success. Items controlled beginning in May 1942 rose an average of 5.4%, while those controlled as of October 1942 rose 28% and uncontrolled items jumped over 49%.

Price Bulletin

Footnote

6

Price Bulletin

Footnote

6

A little boy peers longingly through a store window at a $1,000 loaf of bread, a possible result of rampant inflation. (Folder 8, Box 35, Defense Council Records, OSA)

A little boy peers longingly through a store window at a $1,000 loaf of bread, a possible result of rampant inflation. (Folder 8, Box 35, Defense Council Records, OSA) Some Oregon farmers and businesses were squeezed by the ineffective controls on wages to counterbalance price controls. While passing through Eugene on vacation, Mrs. E.W. St. Pierre, a State Defense Council official, got an earful about the problem from a store clerk: "'Sure we get a lot of business. Everybody goes through here on the way to Portland to get jobs. Price ceilings don't bother us any for when people want food they just go out and buy it. But we are all sold out of melons and we had very few berries or cherries because most of the farmers couldn't afford to pick them, wages are so high.' When I asked how he would solve the problem, he said: 'Well, they put price ceilings on everything else, I don't see why they are scared to put them on wages.'" Other employers faced similar problems as high wages in Portland's shipyards and elsewhere sucked the labor force out of local communities. St. Pierre described the case of the manager of an ice, fuel, and cold storage plant that employed 14 men: "In one week there has been a turnover of 12 men in this plant and he said this situation was typical of all such plants throughout that [Eugene] region."

Footnote

7 Back to the Drawing Board

By April 1943 officials were forced to acknowledge that a more understandable and effective system was needed. Following Roosevelt's "hold the line" executive order on prices and wages to battle inflation, the OPA "embarked upon a completely new program of food price control, a program to replace one which you and I both know is badly in need of revision," according to its director. Armed with new authority, the OPA moved to directly controlling the cost of items as "the simplest and most effective type of price control we can possibly devise."

Footnote

8

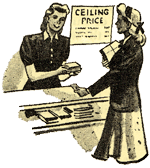

Local price panels met regularly to monitor compliance. (Folder 8, Box 35, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Local price panels met regularly to monitor compliance. (Folder 8, Box 35, Defense Council Records, OSA) Essentially the new price regulations set uniform ceiling prices for an array of foods in each of four classes of stores in a community. The classes differentiated by sales volume between small and large independent and chain stores in terms of the exact ceiling price they could legally charge for an item. Thus, a small independent store (OPA-1) could charge 26¢ for a pound of Crisco shortening while a chain store (OPA-3) could only charge 24¢. The price differences acknowledged advantages, such as economies of scale, that larger chain stores had over neighborhood "mom and pop" stores.

Footnote

9 Critics complained that the price difference would put the smaller independents at a competitive disadvantage against the larger stores but OPA officials rejected this, citing "the most important [reasons of] the convenience of location and the personal relationship between retailer and housewife."

Footnote

10

Volunteers check prices at a Safeway store in Portland. (Image source:

Footnote

14 )

Volunteers check prices at a Safeway store in Portland. (Image source:

Footnote

14 )

Along with other federal actions, such as gaining better control over wages and "the judicious use of Government subsidies," changes to the price control program proved effective. Overall from 1939 to 1943 the consumer price index jumped about 24% while from 1943 to 1945 it climbed only 4%. A late 1943 comparison of inflation related to key defense materials showed a dramatic improvement from the World War I failure (see "Inflation comparison" sidebar above left).

Local Board System

The OPA developed a local board system to administer price control and its sister program, rationing, across the country. Eventually, about 5,600 local war price rationing boards formed with 8 to 20 members each, amounting to an August 1943 membership of over 72,000 volunteers. According to an OPA official, "every county and almost every city and town in the entire United States has at least one local board."

Footnote

12 The price panels set up within local boards typically met once a week to keep programs running as smoothly as possible. The panel reviewed complaints from both shoppers and merchants and made adjustments for "fairness and satisfaction." They would give advice to merchants and try to answer consumer questions. And the panel planned educational activity to increase community awareness.

Footnote

13

Price panel assistants also went into stores to check compliance. These assistants had a list of four to seven nearby stores to visit and usually would get to each one about once every two or three weeks. A more systematic nationwide check occurred in March 1944 as part of an effort to visit every store in the country to check ceiling prices. After beginning the five-day compliance check in Portland, the district OPA director was pleased with merchant cooperation. While the teams of volunteers found few blatant price violations, they did note that "some dealers reported troubles in grading meat properly but showed a general desire to co-operate when regulations are explained."

Footnote

14 Officials heard many excuses from price control violators: "Some were 'too busy to read regulations.' Others sheepishly professed ignorance of ceiling prices. And several butchers had obviously disregarded regulations because 'everybody else is doing it; why shouldn't I? OPA, with its limited staff will never catch up with me!'"

Footnote

15

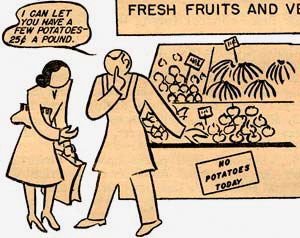

Unscrupulous grocers would try to entice shoppers into the illegal black market. (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA)

Unscrupulous grocers would try to entice shoppers into the illegal black market. (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA) Boards counted on reports from housewives about possible price violations and the OPA offered them shopping advice. Many community newspapers published the OPA's Market Basket Price Book that listed the top prices for various brands and grades of food. Housewives were encouraged to take the lists with them shopping and compare the prices with those posted at stores. If prices were not posted, they were to report the fact to their local board. Above all, shoppers were advised: "DO NOT PAY MORE THAN THE TOP LEGAL PRICE. ...If a higher than legal price is asked, do not buy. The Black Market is not a place...it is a transaction...a violation of the top legal prices. When you find a higher than legal price, bring it to your retailer's attention. It may be an error. If he corrects it, well and good. If not, report the violation at once to your local Board." Since officials relied to a large extent on shoppers to make them aware of possible violations, they wanted to eliminate any fears of bad feelings with the neighborhood grocer resulting from reports: "You are assured that your name will not be used by the Price Panel in investigating the complaint."

Footnote

16 Other Price Controls Kick In

Food stores were not alone as the focus of OPA regulations. Price ceilings were also set on clothing, services, household appliances, fuel and other items. Regional OPA offices had authority to freeze restaurant prices, roll back abnormally high prices, and set specific price ceilings. And the OPA took several steps to stabilize meal prices on trains. As with food stores, price control officials weren't afraid to get into details such as menu items:

The OPA regulated the price of railroad economy meals and train vendor items. (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA) Economy meals are served on all but a few extra-fare all-pullman trains and are priced the same on all lines throughout the country. Here are examples:

The OPA regulated the price of railroad economy meals and train vendor items. (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA) Economy meals are served on all but a few extra-fare all-pullman trains and are priced the same on all lines throughout the country. Here are examples:

BREAKFAST AT 85 CENTS:

A fruit or a fruit or vegetable juice; a choice of hot or cold cereals, eggs, plain or combination omelettes, or an egg with bacon, ham, or sausage, plus plain or toasted bread, butter, and a choice of coffee, tea, cocoa, or milk.

LUNCHEON AT $1.00:

A choice of entrees: meat, eggs, fish and shell fish, chicken, cheese and spaghetti dishes, vegetable plates, salad bowls and cold plates, plus bread and butter, and choice of beverage.

DINNER AT $1.10:

A choice of a casserole meat dish, fish, any cooked form of shell fish, poultry, omelettes, in addition to two vegetables, or cold or vegetable plates; coffee, tea, milk, plus bread and butter.The failure of an operator to provide such meals in sufficient quantities to meet the usual anticipated demand will be considered a violation of the regulation.Footnote

17

Trying to protect soldiers and civilians making short trips, officials also took steps to regulate sales of sandwiches, candy, and beverages made and sold by train "'butchers'" or vendors. In order to reduce these vendor violations, revised regulations required that "maximum prices be posted on the basket or affixed to each item of food or beverage." The OPA also worked to familiarize local military posts with the new train day-coach sales provisions related to vendors "so that men going on leave, furlough or other train travel may be fully aware of their rights and not be 'gypped.'"

Footnote

18

(Image source: Folder 10, Box 35, Defense Council Records, OSA)

(Image source: Folder 10, Box 35, Defense Council Records, OSA) The OPA regulated prices in other areas as well, often leading to journeys into the intricacies of a particular business or trade. Sometimes, instead of raising prices, they allowed suffering types of businesses to offer fewer services for the old price. For example, the Portland office of the OPA issued an "amplifying fact sheet" in November 1943 entitled "Laundries and Dry Cleaners May Eliminate 'Frills.'" OPA officials recognized that these businesses, "faced with wartime problems of labor shortages, equipment and supply shortages, are having difficulty in supplying even the most essential service to the community." The relief meant that "laundries may eliminate, without reducing the prices, such 'frills' as: hand ironing or finishing, ...the use of shirt boards, envelopes, cellophane wrappings; sewing on buttons, and deliveries of more than once a week...." Dry cleaners were allowed to dispense with "untacking and retacking of trouser cuffs" and several other services determined to be "frills." OPA officials also tried to reduce any backlash against the businesses by conditioning customers to the need for the changes: "Housewives are cooperating with laundries and cleaning establishments by accepting these regulations as they have rationing and other wartime measures."

Footnote

19 Related Documents

"Facts You Should Know"

"Facts You Should Know" Statement No. 2, Office of Price Administration, Nov. 1943. Folder 8, Box 35, Defense Council Records, OSA.

"Prentiss Brown's Statement"

"Prentiss Brown's Statement" Speech to Industry Meeting, Office of Price Administration, June 15, 1943. Folder 8, Box 35, Defense Council Records, OSA.

Notes