"Use It Up, Wear It Out, Make It Do or Do Without"

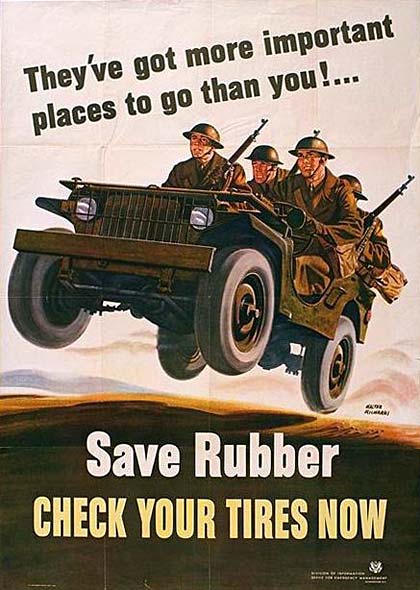

Critical shortages of rubber resulted in a big push for civilian conservation.

Save Rubber poster courtesy Northwestern University Library

Critical shortages of rubber resulted in a big push for civilian conservation.

Save Rubber poster courtesy Northwestern University Library In addition to rising prices, the incredible demands of building and supplying the U.S. war machine led to shortages, black markets, hoarding and calls for conservation. Rationing took center stage in the effort to address shortages but other measures such as conserving existing supplies played important roles as well. People took the wartime slogan of "use it up, wear it out, make it do or do without " to heart. They really had no choice since shortages developed in thousands of different items that were never rationed.

Mobilizing For War

Shortly after its creation in 1942, the federal War Production Board (WPB) sharply curtailed or banned the production of nearly 300 items judged "nonessential" to the war effort. The manufacturers of the targeted products could either choose to convert to the production of items deemed to be essential, or try to make do with substitute materials. Some of the banned items were near and dear to American consumers, who would soon learn the importance of conservation.

By late 1942 the mobilization of production to defense related items was reaching its stride. For example, mechanical refrigerator manufacturers switched to making airplane parts, ordnance and other defense products. A 280 million dollar industry before the war, the industry was projected to handle up to 750 million dollars in war contracts and double its workforce by April 1943. The electrical appliance industry, makers of toasters, waffle irons, coffee percolators and hair dryers, converted almost completely to production of bomb carriers, gas tanks, gun mounts and related items by May 1942. Golf club makers were now making rifle butts and submachine gun grips. Three-quarters of the vacuum cleaner manufacturing capacity was working on 60 million dollars worth of war contracts for incendiary bombs, bomb fuses, gas masks and related items. Production of toys was limited to those that used less than 7% critical materials, while much of the industry shifted production to army cots, ammunition boxes, flares and similar defense products. Other products such as electric fans, fishing tackle, musical instruments and radios were cut off by WPB mandate.

The text with this cartoon reads: "LET THE AXIS STEW! Your Block Leader says: SAVE MEAT!. Our fighters and Allies need it." (Image colorized. Folder 13, Box 29, Defense Council Records, OSA)

The text with this cartoon reads: "LET THE AXIS STEW! Your Block Leader says: SAVE MEAT!. Our fighters and Allies need it." (Image colorized. Folder 13, Box 29, Defense Council Records, OSA)

In addition to banned products, the WPB severely curtailed the output of a range of manufactured goods. By the end of 1942, this diverse collection of items included baby carriages, bicycles, caskets, hot water heaters, fountain pens, hairpins, light bulbs, jewelry, utensils, razors and sewing machines.

Footnote

1 Another household item, the alarm clock, was not available until 1943, when tardy employees drove factory managers to complain to the government, which responded by authorizing the production of a "Victory model" using less metal than previous alarm clocks.

For many, the inconvenience of not being able to replace even such a sweeping array of consumer products paled in comparison to learning they would have to make do without new cars for the duration. The decision was an easy one for WPB officials. The huge automobile assembly plants had become the heart of a mass-production system that would be central to any plans for victory. The fallout from the end of civilian automobile production spread broadly over the country but no business suffered more than the local car dealership. With no new products to market, most dealers were relegated to selling used cars along with maintenance and repair services, leading many to go out of business. Consumer frustration was heightened by the fact that they had plenty of disposable income from the wartime economy and they had weathered a decade of doing without during the Great Depression. Thus, in what must have seemed like a cruel joke to many, society's strong urge to consume was severely hampered by the lack of new products to buy.

Connecting Sacrifice to Victory

These downed flyers were saved by a rubber lifeboat made possible by civilian conservation efforts. (Folder 8, Box 35, Defense Council Records, OSA)

These downed flyers were saved by a rubber lifeboat made possible by civilian conservation efforts. (Folder 8, Box 35, Defense Council Records, OSA) Meanwhile, officials tried to channel much of that frustrated consumerism into positive feelings for the collective war effort and for the millions of men and women serving overseas. A common way to accomplish this was to tie everyday home consumer products with vital defense products. For example, the Marion County Defense Council reminded citizens that tin was in short supply (the Japanese controlled 70% of resource) but was indispensable to the war effort: "TIN - 100% pure TIN - encloses the little individual morphine hypodermic syringe (syrette) which soothes the pain of a soldier lying wounded on the Battlefield." The council pointed out that tin also encased ointments needed to battle infections and soothe burns. Tin coated steel food containers went around the world with the armed forces: "Our Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard are the best fed in the world. TIN makes that possible."

Footnote

2

Officials offered "fun fact" types of information to drive home their point about the connection of consumer goods to war products and the need to conserve and sacrifice. For instance, a set of golf clubs could make one .30 caliber machine gun. A refrigerator could make twelve .45 caliber machine guns while 61 refrigerators equaled one light tank. The aluminum used in one vacuum cleaner could supply enough for seven .50 caliber machine guns or 12 four-pound incendiary bombs. The zinc found in one washing and ironing machine could go toward the production of 20 rifles. Eleven washing machines could produce a half-ton truck. And, the big sacrifice, one automobile would equate to twenty-seven 20mm aircraft cannons. Officials reasoned that the burning need for a new car would subside a bit if the consumer knew their husband or son fighting overseas needed that rifle more than they needed that new car.

Footnote

3

Officials urged people to walk instead of drive to conserve precious resources such as rubber for the war effort.

Woman carrying groceries poster courtesy Northwestern University Library

Officials urged people to walk instead of drive to conserve precious resources such as rubber for the war effort.

Woman carrying groceries poster courtesy Northwestern University Library M.L. Goldschmidt with the federal Office of Price Administration (OPA) provided two more examples to the listeners of KGW radio's "Oregon on Guard" program in March 1943: "What happens to the tires that are not manufactured? ...Why the rubber that we would use for them is employed for military purposes. Our 'Flying Fortresses' roll on rubber---they couldn't take off or land without their huge airplane tires. Still more dramatically, they make the greatest 'Life-Savers' ever turned out by the tire industry, the rubber boats that have already saved hundreds of gallant fliers who were forced down at sea."

Footnote

4

While communicating the demand side of shortages, officials didn't neglect the supply side. For example, sugar was in short supply because boats that previously brought it to America were now carrying supplies to troops and allies in Africa, Russia, Britain and elsewhere. And as the "War-Victory Bulletin" put it, tires were in short supply because "the United States, the world's greatest consumer of rubber, obtained all but a few shiploads of the precious material from Malaya, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Ceylon and the other lands of the Middle East in 1941. Rubber is slow growing. It grows slower than wars are won." Government efforts to produce synthetic rubber eventually paid off and by 1944 synthetic rubber accounted for nearly 90% of the total used. Still, the rubber shortage caused headaches for military and civilian planners in the first part of the war. As a result, officials decided to regulate the supply of gasoline even though it was not in short supply, reasoning that controlling the use of cars would save on precious rubber.

Footnote

5 The Car at the Center of It All

The month after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Mrs. Mortimer Hartwell of the Oregon State Defense Council was in high schools giving speeches about adjusting to life on the home front during the new war. She had strong comments and advice on the role of the automobile in society and how it fit in the need for conservation:

I said to someone the other day: "Nothing is going to hit us Americans harder than being curtailed in our automobile driving." We are spoiled and we also have built up our whole lives on the idea that we have a car. We must now learn to walk and patronize public conveyances; we must ride bicycles - we must do this cheerfully and ungrudgingly. We must take care of the car we have and use it for

necessary driving. We are short on rubber, and though we have plenty of gasoline, it must be used in transportation of war materials and men and in other lines of endeavor vital to war service.

Here again you boys and girls can help. Don't beg for the car. My family was on its way to lose the use of its legs. The limit was arrived at when my two Scouts wanted to be driven half a mile to [a] Scout meeting!Footnote

6 "The War Against Waste - Conservation"

People needed to learn to care for their rubber products, such as these boots, to make them last longer and conserve the valuable resource. (Folder 47, Box 27, Defense Council Records, OSA)

People needed to learn to care for their rubber products, such as these boots, to make them last longer and conserve the valuable resource. (Folder 47, Box 27, Defense Council Records, OSA) Conservation was an important element of the strategy to combat shortages, and many measures were destined to be unpopular. One prescription called for the use of substitutes for items in short supply. Consumers were encouraged to use honey for sugar, corn oil for olive oil, cotton or rayon for wool, paper containers instead of tin; and wood furniture instead of metal. They were asked to simplify by eliminating the "frills in consumer goods." Examples included fewer models, sizes, colors and styles - even the "elimination of cuffs on men's trousers." So called "Victory suits" with several such features that conserved wool were promoted as patriotic fashion.

Footnote

7

Since their refrigerators, washing machines, and cars could not be replaced with new models until after the war, citizens were asked to learn how to maintain and repair equipment to make it last and keep it running efficiently. For example, the "'handy man' about the house" was encouraged to keep the furnace clean and the hot water heater free of rust and sediment. The homemaker also got plenty of suggestions for stretching the life of short resources. She was reminded to vacuum rugs often because "dirt is the enemy of carpets and rugs." Moreover, she was told that "a pad, or even newspapers placed under a rug will lengthen its life." Officials gave sound advice in the kitchen too: "Don't use the oven to heat the kitchen unless you have to." Other words of wisdom included: "Don't overcrowd your refrigerator," "Don't open [refrigerator] door too frequently - always close quickly," and "never place the heating unit of any appliance in water."

Footnote

8

Girdles warranted special care and experts suggested "frequent, rather than hard laundering." Women were also cautioned to "use care in putting on and taking off rubber undergarments. Stretch and strain will shorten their life."

Shortages spawned a small industry in advice on how to maintain and repair clothing, shoes and other items. And with the severe shortage of rubber, officials once more reminded citizens that "making rubber articles last longer is a real part of our war-time duty." The Better Business Bureau of Portland prepared detailed care instructions for a range of common rubber products. They offered advice on the storage of rubber items: "Heat and sunlight shorten the life of rubber. Clean and dry thoroughly a rubber or rubberized article before storing it...." They also wisely suggested storing rubber "away from hot pipes or chimneys." Items such as rubber overshoes were not to be left outside while people were cautioned to "avoid bending, kinking and dragging garden hose[s] over rough surfaces of any kind." Girdles warranted special care and experts suggested "frequent, rather than hard laundering." Women were cautioned to "use care in putting on and taking off rubber undergarments. Stretch and strain will shorten their life."

Footnote

9 Going Too Far With Conservation?

"He admonished his audience that 'their government expected them to wear their clothes so long as they would cover the body and keep the wearer warm.' He further stated that 'he hoped it would very soon be fashionable to be shabbily dressed in Portland,' (He himself was nattily attired in a dinner jacket with the latest accessories.)"Footnote

10

Some thought the conservation effort was going too far. E.P. O'Neill, president of the Retail Trade Bureau in Portland, fired off a complaint to Governor Sprague about what he thought was outrageous advice given by state officials: Our Bureau's attention has been called, on several occasions, that a Mr. Eugene Burdick, speaking under the auspices of the Oregon Defense Council, appeared before the East Side Commercial Club urging citizens not to buy, among other things, any new clothing."...

Conservation helped this blue-ribbon steer go to war...as meat. (Folder 13, Box 29, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Conservation helped this blue-ribbon steer go to war...as meat. (Folder 13, Box 29, Defense Council Records, OSA) O'Neill's complaint earned a sharp reply from the director of consumer interests for the State Defense Council, Mrs. E.W. St. Pierre. She just happened to have a transcript of Burdick's speech in her office and quoted from it to make her point that he had been "misquoted and misunderstood": "Mr. Burdick - 'If you are among the fortunate ones who have a large and adequate supply of clothing and some of the household necessities and gadgets, do not replace them. It is very difficult to ask those who have been unemployed for a long period and are just now beginning to be able to purchase much needed clothing and household equipment to stop buying. Denial and sacrifice must come first from those who have long enjoyed the comforts...Mend and care for your clothes and shoes as never before...'"

Government officials always had to balance the needs of numerous constituencies, such as the retail clothing industry, but St. Pierre wanted to be sure she put the issue in perspective for O'Neill: " I feel we are a nation fighting with our backs to the wall. All elements of personal profit must be subordinated to preservation of our way of life. The best blood of the nation cannot flow in rivers while we at home carry on business as usual and refuse to sacrifice so much as an extra Easter bonnet."

Footnote

11 Related Documents

Letter from E.P. O'Neill to Governor Sprague

Letter from E.P. O'Neill to Governor Sprague, Feb. 16, 1942. Folder 6, Box 28, Defense Council Records, OSA; Letter from Mrs. E.W. St. Pierre to E.P. O'Neill, Feb. 18, 1942. Folder 6, Box 28, Defense Council Records, OSA.

Notes