United States Food Administration

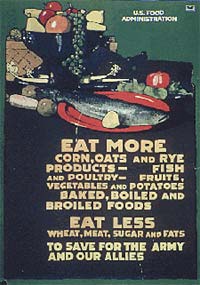

Americans were encouraged to change their eating habits to help the war effort. (Image, National Archives)

Americans were encouraged to change their eating habits to help the war effort. (Image, National Archives)

In August 1917, the federal Food Administration began taking measures designed to conserve food for the war effort. Americans were asked to reduce their consumption of wheat, meat, sugar, and fats in particular. The administration set up a nationwide structure that reached down to the county chairman level to oversee compliance on the local level. Generally, the system relied on the patriotic good will of the population to meet the goals of conservation. But strict rules backed up the effort and kept people honest.

Restrictions on Wheat

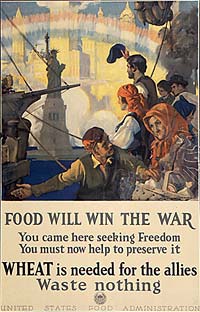

Restrictions on the use of wheat were felt by households across Oregon. The government standardized the size of loaves of bread made by bakeries. Only bread baked with the exact percentage of substitute ingredients as required by the food laws could be called "victory bread."

Substitution became a familiar part of the home front experience as necessity became the mother of invention. Corn, barley, rice, oat, rye, potato, and other flours appeared in breads. In order to get a small sack of white wheat flour, a shopper had to buy an equal amount of non-wheat flour. Recipes for bread and other typically wheat-based products recommended no more than 50% white flour. Some Oregon families saved their "pure white bread" for once a week meals. Others observed "Wheatless Wednesdays." In Grass Valley conservation was reinforced when "Hoover cards and pamphlets were distributed among the housewives for use in the kitchen."

These "victory breads" and similar recipes proved to be a mixed blessing as one observer noted: "Many people got indigestion and numerous other ailments from this way of living, it is not so much what they ate as the way it was put together. And then there is the other side, many people regained their health from the course foods and declare that never again will they eat bread made entirely of whole wheat flour."

Limiting the Use of Sugar

The Food Administration also limited the use of sugar. It originally allowed two pounds per month per person but the restriction was later moderated, allowing families more sugar as the government adjusted its war needs. Moreover, additional sugar could be used for canning fruit, as officials recognized the overall conservation value of preserves. In order to purchase sugar, shoppers had to present the merchant with a card issued by the county food administrator. Retailers and wholesalers were required to sign certificates stating they would follow the food laws related to the sale of sugar.

The U.S. Food Administration saw the conservation of wheat as a top priority. Immigrants to America were asked to help preserve their much valued freedom. (Image, National Archives)

The U.S. Food Administration saw the conservation of wheat as a top priority. Immigrants to America were asked to help preserve their much valued freedom. (Image, National Archives)

Substitutions filled the sweetener gap as honey and various kinds of syrups made their way into recipes formerly calling for sugar. Sugarless gum was developed during World War I. To underscore the value of conserving sugar, one estimate claimed that "the cost of the yearly consumption of candy in the United States per year is double the amount needed to supply Belgium with food for one year."

Uncle Sam's Kanning Kitchen

Many Portland residents volunteered to work for Uncle Sam's Kanning Kitchen, a department of the National League for Women's Service. The kitchen was organized in June 1918 to assist the federal Food Administration in the conservation of fruits and vegetables. Under the direction of general manager Miss Ruth Guppy, the organization preserved 15,000 quarts of fruit that otherwise would have been wasted.

The kitchen had help from 52 clubs and sororities during its four month run. In the cherry season, up to 100 women and children were taken by Army trucks and its own motor pool to orchards where they picked over a ton of fruit a day. Cherries were sorted and "turned over to an experienced corps of lieutenants who canned and made jam, jelly, butter, and preserves."

In addition to picking fruit, the kitchen benefited from donations from the city markets and commission houses. Tons of this fruit were sent fresh to the Vancouver Barracks Hospital, Benson Polytechnic Hospital, and local charities for children.

Eating more fish would conserve meat for the troops and allies. (Poster at Oregon State Archives, original at National Archives)

Eating more fish would conserve meat for the troops and allies. (Poster at Oregon State Archives, original at National Archives)

Among the statistics recorded by the group: the largest donation was 11.5 tons of pears; the largest amount canned in one day was 815 quarts of cherries; and on two occasions the group picked and canned 2.5 tons of cherries.

Other Conservation Adjustments

While wheat and sugar took center stage in the conservation effort, Oregonians adjusted in other ways as well. They ate more fish and poultry instead of meat as "Meatless Mondays" entered the routine of many in the state. They used various types of vegetable oil instead of lard. Since woolen clothes were in high demand for the war, "it was deemed more patriotic to do without" them. Oregonians also made do without or with less of certain drugs, chemicals, and fuels that were in short supply because of the war.

Hood River schools were among many in the state that worked to secure food savings pledges from local residents. Their effort yielded pledges from 99% of the county's families. In the process, the schools sent out over 2,000 letters, educating residents on the need for savings and methods to conserve food. Conferences held by teachers and food dealers rounded out the efforts.

Oregonians also tried to produce more food locally during the war. The government had taken over the railroads and given preference to shipping war necessities. This left many communities with fewer fruits and vegetables than they received before the war. In response, many people grew "war gardens." One Klamath Falls observer noted that "since the war, everyone who has had a plot of ground has had some sort of a garden and altho [sic] this seemed small in itself it saved a great deal as a whole."

Notes

(Oregon State Defense Council Records, State Historian's Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 38, 52; Publications and Ephemera, Box 8, Folder 1)